Uber’s record on safety is clear

Written byA recent article has made startling claims suggesting that Uber has turned a blind eye to the safety of passengers and drivers. Nothing could be further from the truth. Safety is a core value at Uber, and we have invested billions of dollars and countless hours to reduce safety incidents during trips, particularly when it comes to sexual misconduct and assault.

The challenge is enormous, but I believe Uber has done more than any other company to confront it. More than half of women in the US have experienced sexual violence in their lifetimes. Uber is not immune to this deeply ingrained and troubling problem—it persists across all parts of life and modes of transportation—but that hasn’t stopped us from continually strengthening our technology, policies, and procedures to improve safety.

Our approach is making a difference: reports of serious sexual assault on Uber have fallen by 44%.* We were the first—and, unfortunately, still one of the only—companies to publish this kind of data publicly, because we believe in transparency and want to be held accountable for progress.

Some have asked why we haven’t been able to stop more bad things from occurring. With more than a billion Uber trips happening every month, safety incidents will happen too, even if they are exceptionally rare. But rare doesn’t mean acceptable. That’s why we’re constantly working to make every trip safer.

We believe Uber is one of the safest ways to get from A to B, with more than 99.9% of trips ending without any issue. But you won’t hear us say our work on safety is done, or that we get it right every time. That’s why we’ll continue to listen to feedback, push harder, and innovate more to make every trip better, every single day.

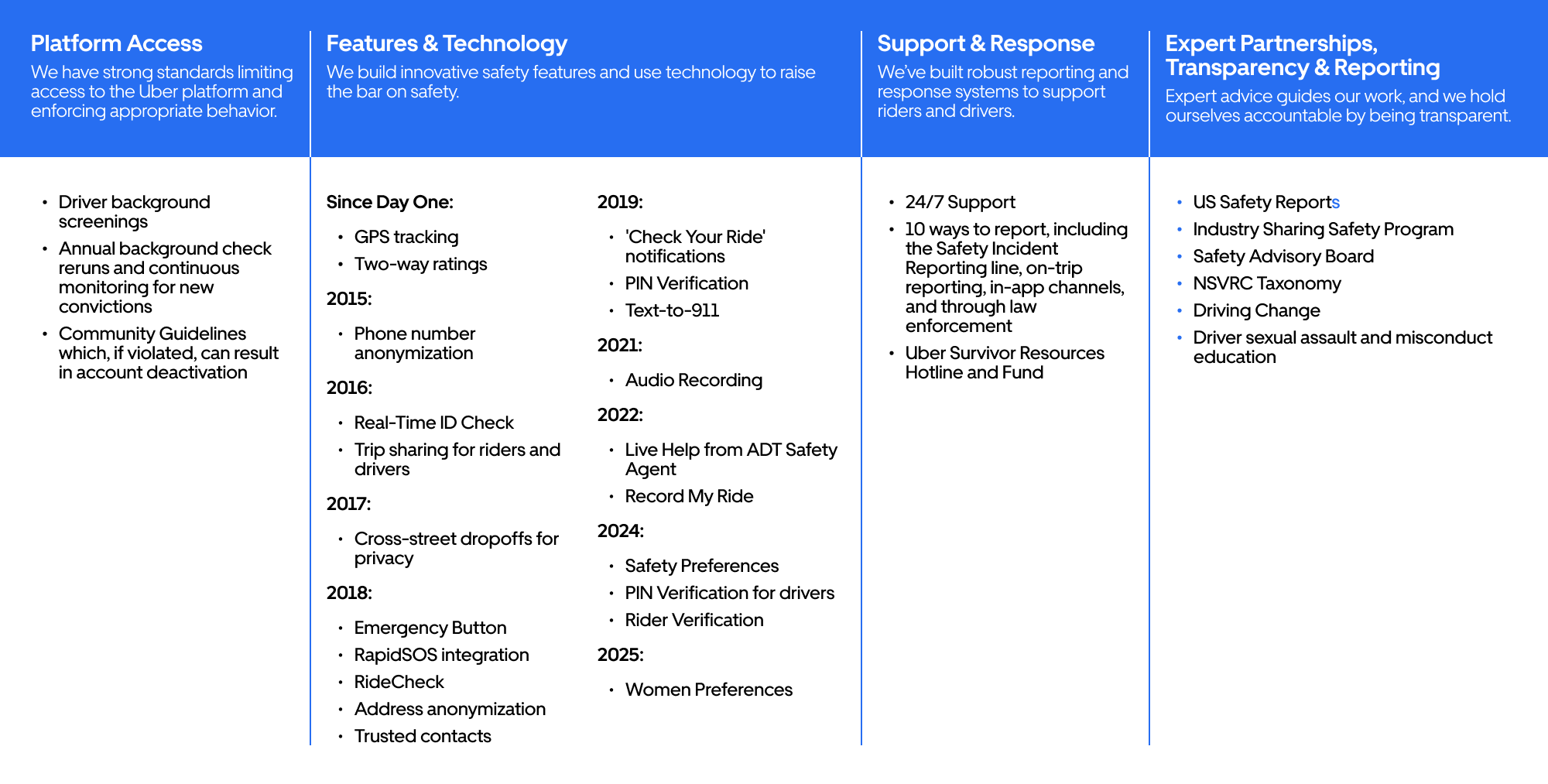

Uber has led the way on safety, innovating and improving across a range of areas:

Is it true that Uber hid data on 400,000 sexual assaults on its platform?

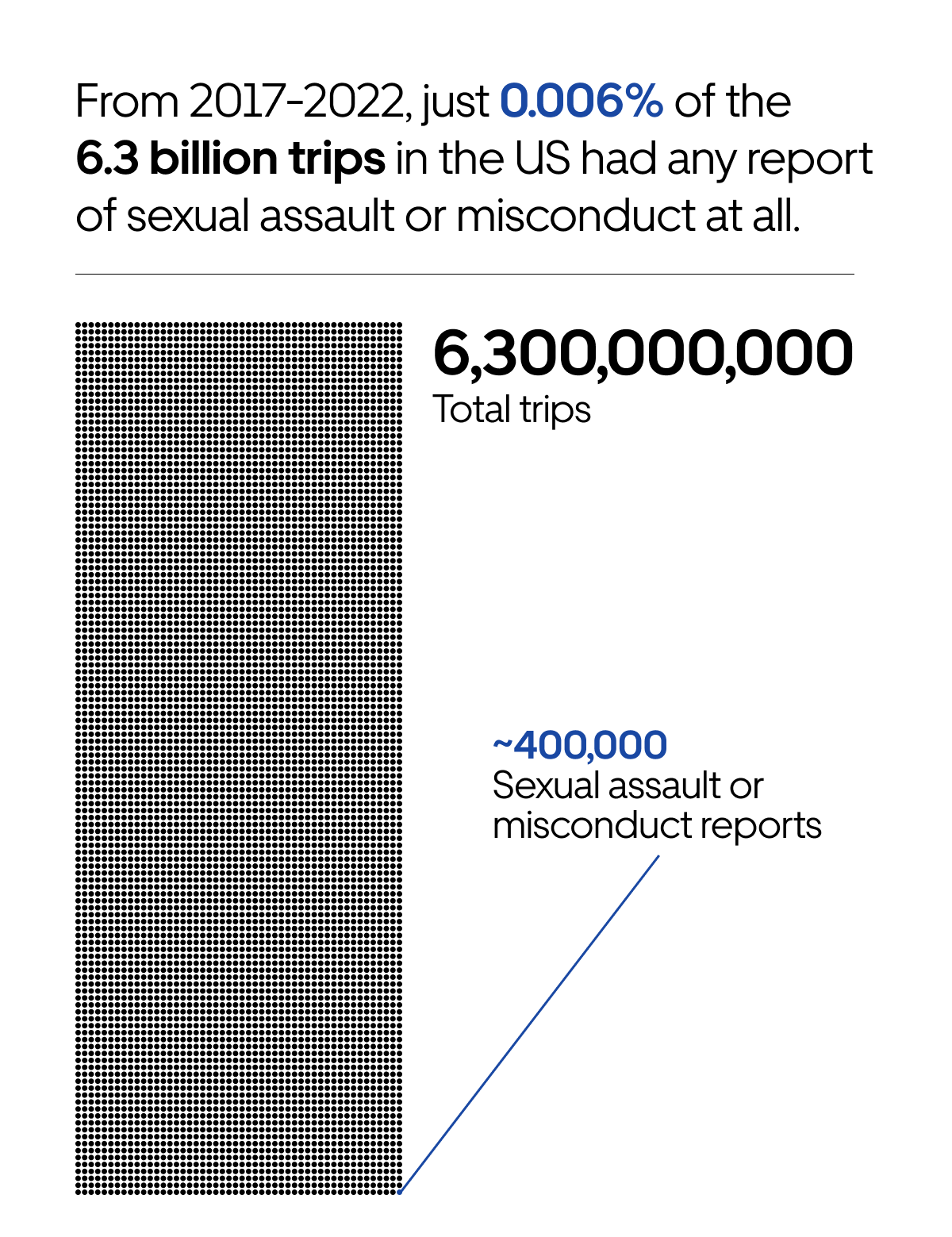

No. As part of an ongoing lawsuit, Uber provided data on the total number of trips with reports of sexual assault or misconduct submitted by riders, drivers and third parties over the course of 6 years from 2017 to 2022.

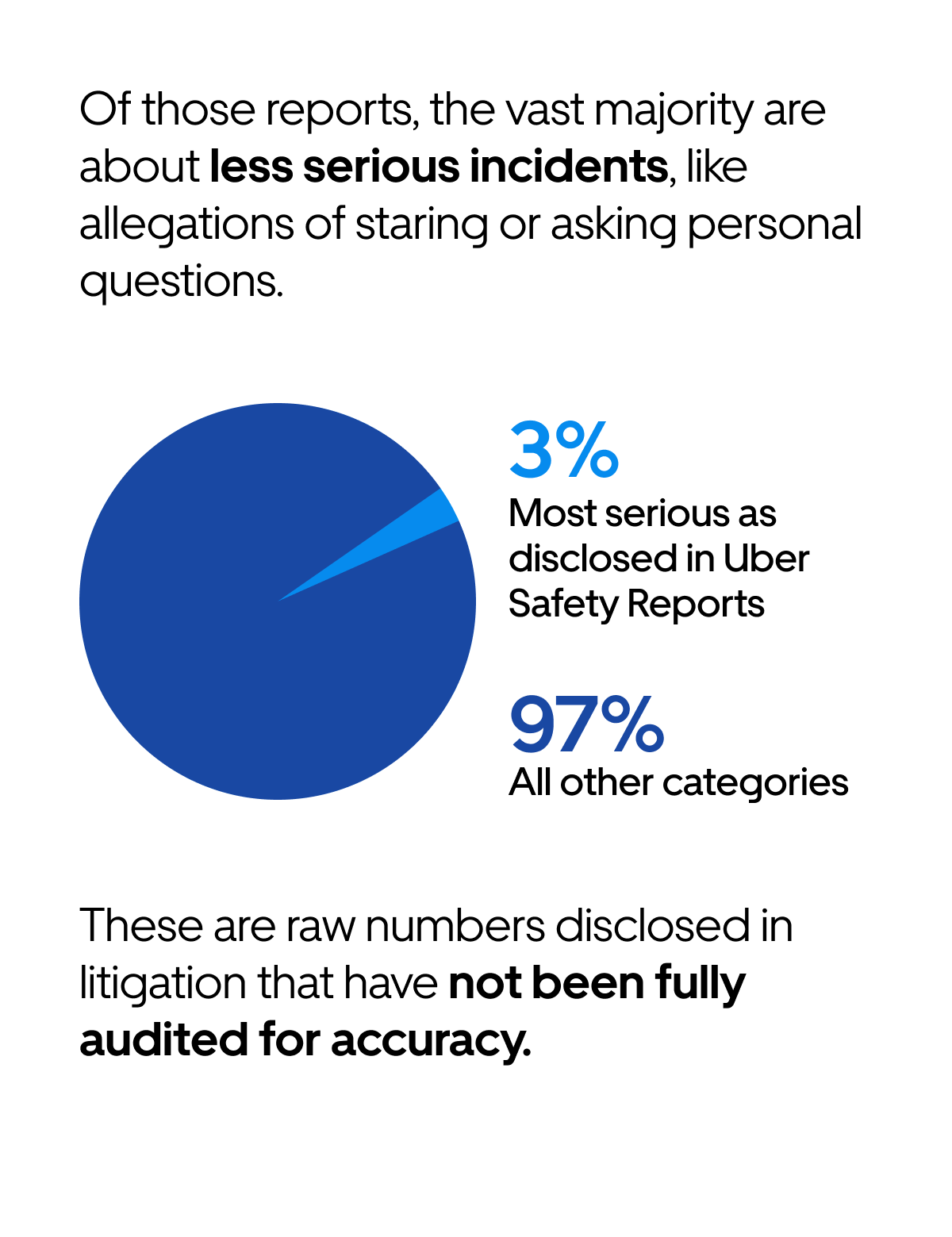

First and foremost, the vast majority of the reports cited were less serious and non-physical in nature and did not fall into the category of sexual assault—such as comments about someone’s appearance, flirting, staring, or inappropriate language.

Furthermore, most of the approximately 400,000 reports are unaudited, meaning they haven’t gone through the same rigorous vetting process as the data included in our Safety Reports. That process accounts for incorrect and mistakenly categorized reports, as well as false reports submitted with the goal of getting a refund (which unfortunately does happen).

Finally, these reports were exceptionally rare: during that same time period, 6.3 billion Uber trips took place in the United States, meaning all of the reports amounted to just 0.006% of total trips. The most serious reports were even rarer, at 0.00002%, or 1 in 5 million, of all trips.

.

.

It’s not an exaggeration to say that Uber has been more transparent on the issue of sexual assault than any other corporation. We have always felt the first step to addressing the problem is by talking openly about it and bringing data to bear. That’s why we put out a first-of-its-kind Safety Report in 2019, and have since published two more.

When we set out to publish our first report, we found there was no common way to categorize reports from drivers and riders about these types of incidents. So we worked with experts to create one, which includes 21 categories.

We publicly report on the 5 most serious categories of sexual assault reports. That’s because those categories are the least subjective, meaning we can have a high degree of confidence in the data. Less serious reports—like flirting, staring, or making inappropriate comments—are more subjective, often less detailed, and harder to consistently categorize.

It’s important to say that just because we don’t publicly disclose a certain type of report doesn’t mean we don’t do anything with them. On the contrary, we track feedback closely and if, for example, we receive multiple safety reports, even if they are less serious, we will take swift action to ban that driver or rider from Uber.

What is S-RAD and why don’t you use it to predict and prevent high-risk trips on your platform?

For the past several years, we have used data to inform our trip matching algorithm in an attempt to make better matches between drivers and riders. This technology is internally called Safety Risk Assessed Dispatch, or S-RAD.

Here’s an example of how this technology works: if a brand-new rider requests a late-night trip in an area known for nightlife, our matching algorithm may prioritize more experienced drivers with a strong record of late-night trips and positive rider feedback.

While S-RAD (and indeed anyone) cannot reliably predict crimes before they happen, we’ve found prioritizing better matches can help avoid interpersonal conflicts. In fact, this technology has helped to reduce sexual assault and misconduct report rate by 10% since it launched, part of the overall drop of 44% from 2017-2022.

While S-RAD is an important tool in our toolkit, it’s not a silver bullet. It can only go so far because the overall rate of serious incidents is so low (1 in 5,000,000 for the most serious) and human behavior is inherently unpredictable. So while it can reduce incidents in the aggregate, it cannot reliably predict whether an individual pairing or trip will result in an incident or not.

S-RAD does not flag “high risk” drivers but rather works to improve the trip pairing to reduce the chances of interpersonal conflict between the driver and rider. S-RAD evaluates trip pairings at a detailed level, because these are extraordinarily rare incidents that we are trying to make even rarer. The fact we are evaluating risk at such a granular level is a testament to the broad suite of technology and policies we have in place.

Unilaterally blocking certain types of trips that the technology may consider more risky, like all requests from bars late at night, would leave many people stranded on the street, encouraging them to drive drunk or walk home unsafely. Instead, we seek to prioritize better matches to reduce overall risk.

Uber claims to be on the side of survivors, so why are you fighting them in court?

It’s important to emphasize the difference between the litigation process, which is adversarial by design, and Uber’s internal process when a sexual assault is reported to us. Our internal processes were developed with input from safety experts and are designed to be survivor-centric. We rely heavily on the survivor’s statement of experience, which we take at face value. Unlike the court system, we do not require proof of the incident in order to take action or provide support. And we have a dedicated hotline and resources fund for sexual assault survivors, in partnership with experts at RAINN.

The court cases we are currently engaged in (one of which gave rise to this article) are the result of Uber having been one of the first companies to waive mandatory arbitration for individual claims of sexual misconduct. We understood at the time that taking such a step could open the door to mass lawsuits. We still feel strongly it was the right thing to do, because we wanted to give survivors control over how they pursue their claims—whether privately in mediation or arbitration, or publicly in open court. All of the plaintiffs in this case chose open court. Just as plaintiffs have a right to make their case, the defense has a right to investigate and respond to those claims.

Don’t comments from Uber’s own employees indicate the company doesn’t take safety seriously?

No. A handful of internal messages from several years ago, taken completely out of context, are simply not representative of how seriously we take the issue of safety. We have invested billions of dollars over the years in this area, and have thousands of people who work on safety, day in and day out.

*From 2017 through 2022. See our latest Safety Report.