How Uber Conquered Database Overload: The Journey from Static Rate-Limiting to Intelligent Load Management

January 13 / Global

Introduction

Uber’s thousands of microservices handle traffic for over 170 million monthly active users: riders, Uber Eats users, drivers, and couriers. At the heart of this infrastructure are Docstore and Schemaless, Uber’s in-house distributed databases built on top of MySQL®. These databases span thousands of clusters, store tens of petabytes of operational data, and serve tens of millions of requests per second with billions of rows read or updated. They back some of the most latency-sensitive and mission-critical workloads, powering every business vertical at Uber: from rides and deliveries to maps, payments, and beyond.

At this scale, even minor overloads aren’t isolated events, they cascade. A brief spike in one part of the system can ripple outward: downstream services time out, retries pile up, and degradation amplifies into broader failure. In a multitenant environment, it’s also critical to ensure fairness and prevent any tenant from hogging all the resources. With workloads varying in traffic shape, latency profiles, and system impact, building effective overload protection is a uniquely challenging problem.

The cost of getting overload protection wrong is steep. This blog shares how we built an intelligent load manager that detects overload from multiple signals to keep our databases stable and fair under pressure.

Docstore and Schemaless

Before diving into the load manager that protects Uber’s databases, let’s walk through their architecture.

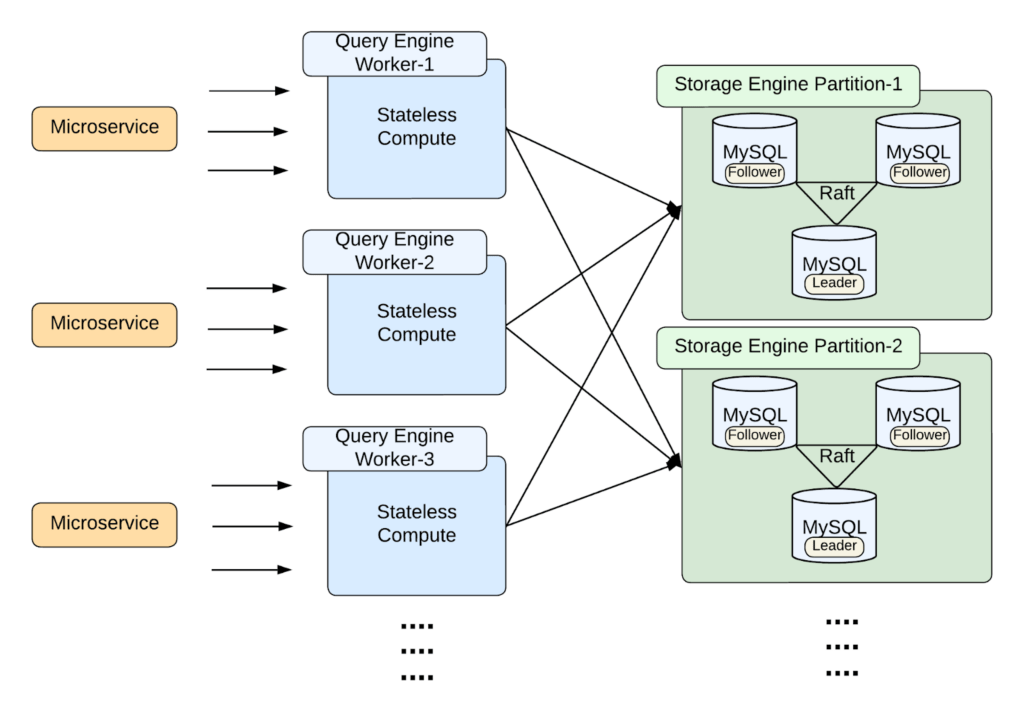

While Docstore supports transactions with full CRUD operations and Schemaless is optimized for append-only workloads, both share a common architectural foundation. It comprises three primary layers: a stateless query engine, a stateful storage engine, and a control plane. For the scope of this blog, we’ll focus on the query and storage engine layers.

The stateless query engine is responsible for query planning, request routing, sharding, schema management, authorization, request parsing, and validation. It serves as the routing layer: coordinating and validating client requests before handing them off to the storage layer.

The stateful storage engine handles transaction management, connection pooling, consensus, and replication. Data is sharded across multiple partitions, with each partition consisting of one leader and two followers, coordinated via Raft to ensure strong consistency. Each partition is backed by MySQL nodes with locally attached NVMe SSDs, built to support high-throughput, low-latency workloads at scale.

Challenges

Quota-Based Rate Limiting in the Query Engine Layer

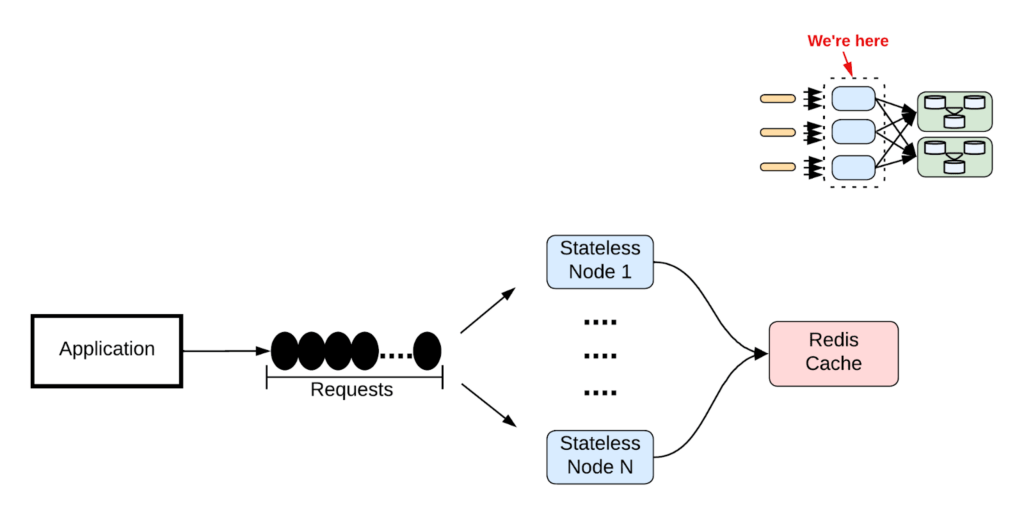

Initially, we explored a quota based rate-limiting approach within the stateless query engine layer. The concept was simple: assign each read and write request a capacity unit cost based on bytes processed, grant users fixed quotas, and return a 429 when those quotas were exceeded. Since routing nodes were stateless, we stored quota usage in a central Redis® cache. While conceptually sound, this approach didn’t hold up in production.

First, it added unnecessary complexity. Every request required a Redis call, introducing a new point of failure and the overhead of an additional network hop.

Further, for the stateless routing layer to accurately shed requests for an overloaded storage partition, it’d need to maintain realtime health and load information for thousands of partitions across the system. This introduced a lot of tracking overhead, undermining the scalability of the architecture.

The cost model was also too imprecise. In Docstore and Schemaless, due to the way MySQL handles scanning and filtering, a query that performs a full table scan but returns a single row was assigned the same capacity cost as a query that only reads a single row. This fundamental flaw in our metering meant that lightweight and heavyweight operations were treated the same, making quota enforcement unreliable.

Finally, quotas were defined statically, resulting in frequent requests from stakeholders to adjust their quotas, making them ineffective in multitenant environments.

Despite its initial promise, this approach failed. But it gave us a crucial insight: overload management must live as close to the storage nodes as possible. That realization became a cornerstone of the final design in the stateful storage layer.

Identifying the Right Signal for Overload

A core challenge in designing a resilient load manager is choosing a reliable signal for overload. Simple QPS-based rate limiting is too coarse. It fails to account for workload variability, often shedding too late or too early. What can be more effective is concurrency: the number of operations currently in flight. It directly reflects system load, following Little’s Law: Concurrency = Throughput × Latency. In stateful systems, it maps closely to resource usage, making it a more dependable indicator.

Balancing Resilience and Fairness

Balancing resilience and fairness is a core challenge in multitenant systems. During system-wide stress, we want to shed traffic by priority, dropping low-priority requests first. But when a single noisy actor hogs resources without triggering global overload, we also need per-tenant rate limiting that works independently of the system load. This dual requirement led us to combine dynamic overload detectors with fairness enforcement mechanisms that operate in parallel.

Building the Foundation of a Unified Load Manager

Controlled Delay: Smarter Queuing Under Pressure

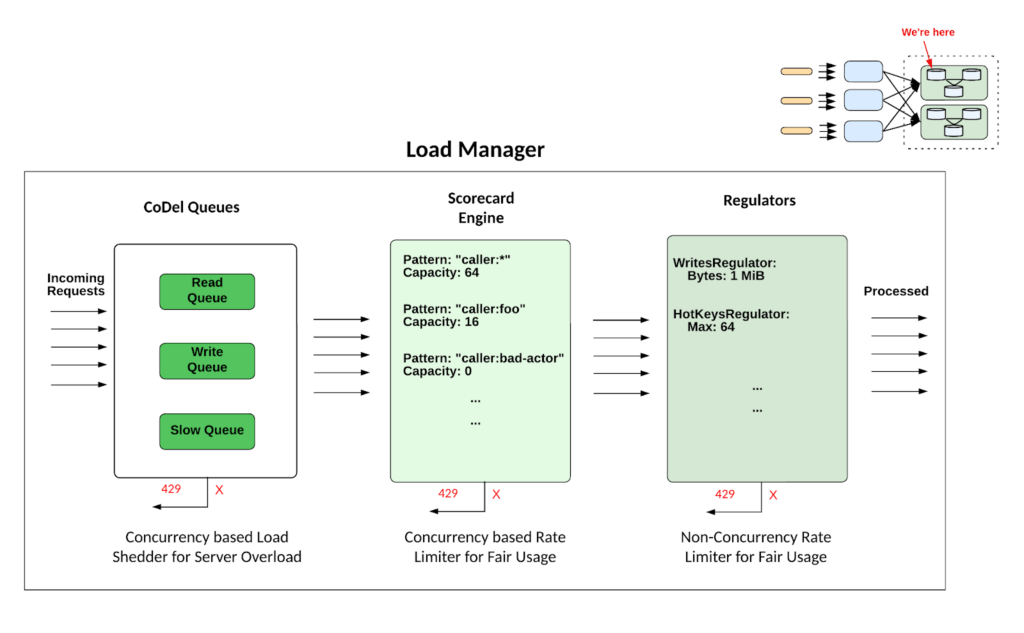

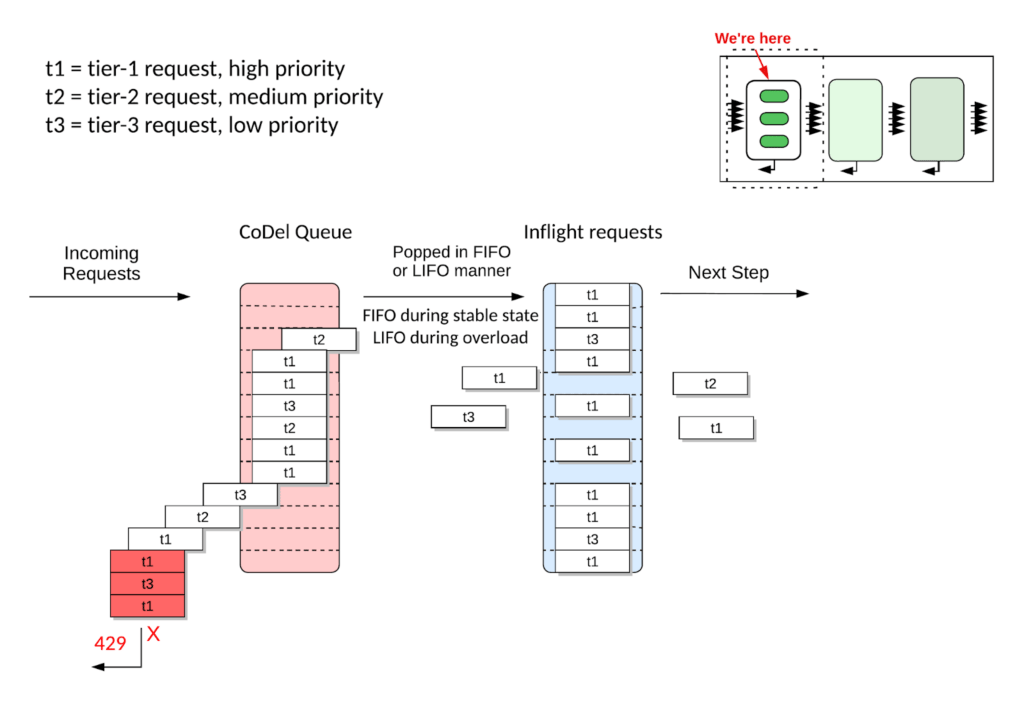

The load-shedding journey began with CoDel (Controlled Delay), a concept borrowed from networking to combat bufferbloat. Instead of shedding based on queue length, CoDel looks at how long requests wait in the queue: favoring responsiveness over volume.

We implemented separate CoDel queues for each operation type:

- Read queue: for point lookups and light queries

- Write queue: for insert, update, and upsert operations

- Slow queue: for long-running and background operations like scans, deletes, or replication

Each queue was managed independently, giving us better isolation across workloads.

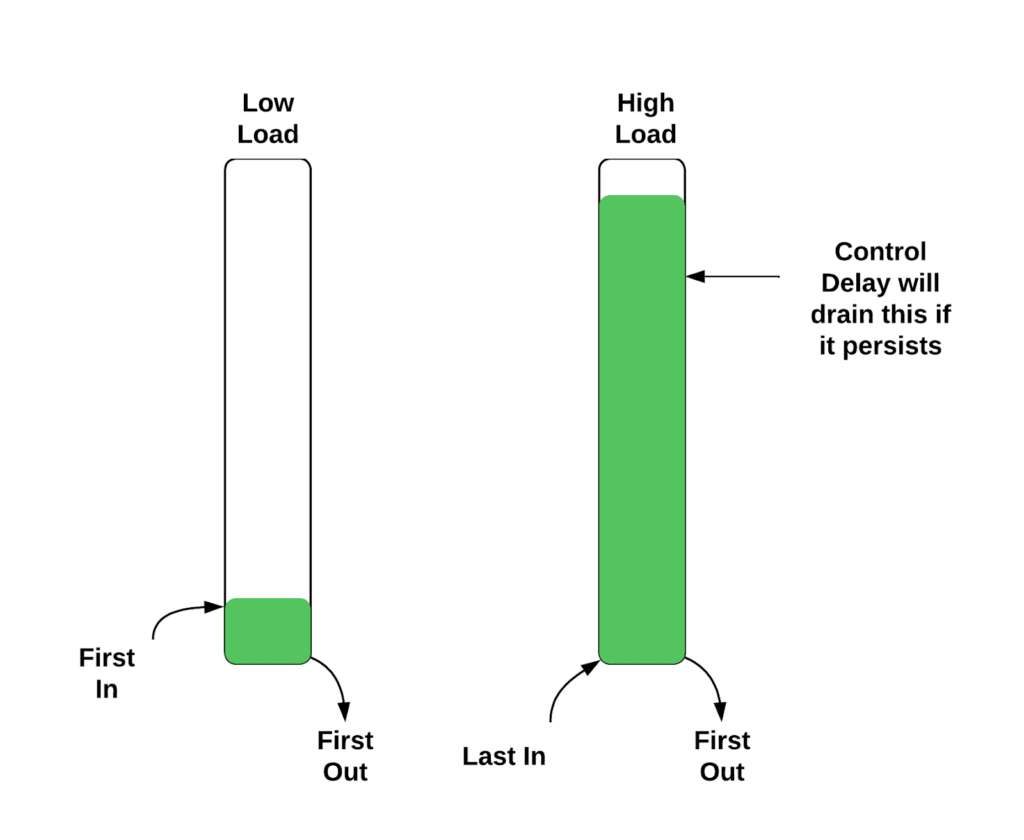

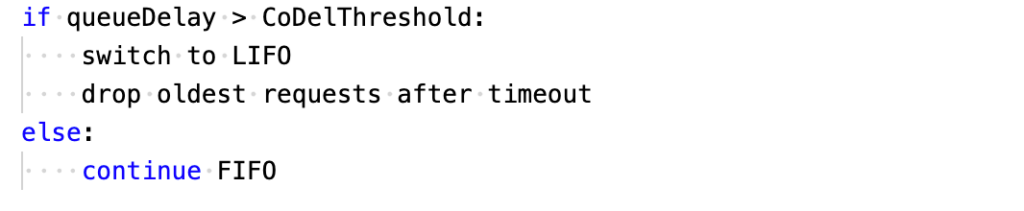

FIFO queuing wasn’t enough because a pure FIFO queue processes requests in arrival order, which works well when traffic is stable. But under overload, FIFO creates a trap: old requests accumulate, wait too long, and often get abandoned or retried by the client. This results in wasted work. Meanwhile, fresh requests, still relevant and likely to succeed, sit idle at the end of the line.

CoDel introduces adaptive LIFO to solve this. Figure 5 shows how it works.

Under normal load, the queue behaves as FIFO. Under pressure, it switches to LIFO, favoring newer requests that still have a chance to succeed. This simple shift improves responsiveness by failing fast, shedding stale work, and giving fresh requests priority.

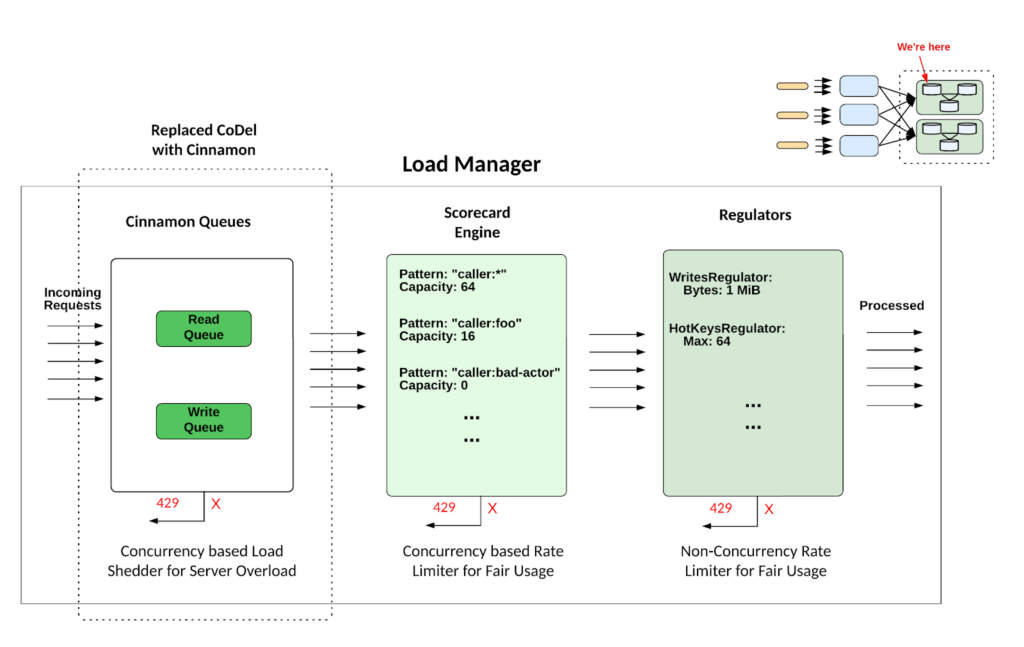

Scorecard Engine

The Scorecard engine is a rule-based admission control component and a lightweight quota system designed to enforce per-tenant concurrency limits in multitenant environments. While load-shedding protects the system during overload, Scorecard ensures that no single tenant can dominate shared infrastructure, even in normal conditions.

The configuration is simple and deterministic.

The primary benefit of the Scorecard lies in incident containment. It helps pinpoint the source of disruption during outages or traffic spikes. It isolates and caps misbehaving tenants without disrupting others, balances stability during normal load with strict limits under stress, and reduces blast radius during overload events by enforcing boundaries quickly and deterministically.

The Scorecard provides predictable fairness and blast radius control, especially when multiple tenants are competing for shared resources.

Regulators

While Scorecard protects against concurrency-based overuse, it doesn’t cover all the ways a stateful database system can overload. Some forms of skews are subtle. They don’t show up in concurrency saturation, but they can still degrade system performance if left unchecked.

For example, a low QPS caller can still overload the system by sending large write payloads. Or, traffic skewed to one partition key can overload a single cluster while others sit idle.

To guard against these skewed behaviors, we introduced plug-in regulators: node-local overload detectors that enforce invariants the system mustn’t violate. They rarely trigger during healthy operation, and that’s by design. At the same time, when users accidentally create hotspots or large data ingestions, regulators kick in to prevent cascading failures.

We use these regulators:

- Write bytes regulator: Limits concurrent write volume to prevent I/O saturation

- Partition key regulator: Throttles traffic targeting hot partition keys

- Memory regulator: Tracks free process memory and throttles when we’re low on memory

- Goroutines regulator: Tracks total number of goroutines and throttles when it exceeds threshold

What Worked Well

By shedding excess requests, our CoDel queues prevented runaway resource exhaustion, which led to improved stability and a higher success rate for accepted requests. This approach was particularly effective at ensuring that core system functionality remained available during overloads.

The Scorecard engine successfully isolated misbehaving tenants by enforcing per-tenant concurrency limits. This allowed us to quickly contain disruptions from noisy neighbors without penalizing other users, ensuring that shared resources were used fairly.

Limitations

While this initial setup laid the foundation for overload protection and fairness, it came with a few limitations. First, CoDel treated all requests equally, dropping low-priority and user-facing traffic alike, leading to a bad customer experience and increased on-call load.

CoDel also relied on fixed queue timeouts and static inflight concurrency limits, which can be a low-fidelity solution for a dynamic system, requiring frequent manual tuning and leading to operational toil.

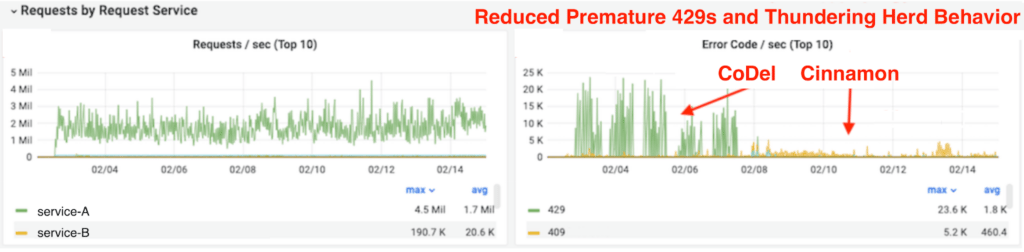

The fixed, static wait times in CoDel led to a thundering herd problem. When requests were eventually rejected, they’d all retry at once, triggering repeated cycles of overload and rejection. During these periods, the lack of traffic differentiation meant even high-priority requests were dropped, leading to customer-visible errors and amplifying the blast radius.

Ultimately, it kept things from breaking, but lacked the nuance and dynamism required for a high-quality user experience. This highlighted the need for dynamic and priority-aware queues.

Evolving the Architecture

Cinnamon Replaces CoDel

We observed that many overloads stemmed from low-priority, asynchronous jobs: pipelines, aggregators, and internal garbage collection flows. These shouldn’t have the same survivability as ride requests or real-time pricing queries.

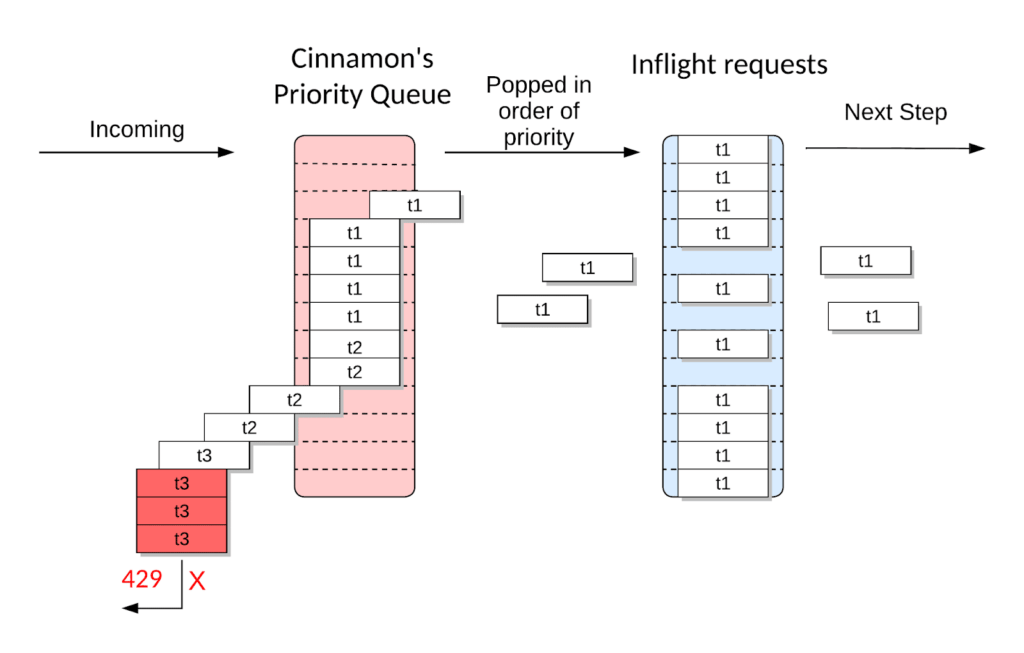

To address this, we replaced CoDel with Cinnamon, a priority-aware load shedder developed by the Delivery team at Uber. Cinnamon makes smarter shedding decisions by considering request rank, dynamic system state, and the relative importance of workloads.

Request rank is derived from the priority attached to the request, and if no explicit priority is present, Cinnamon assigns a default based on the calling service. Priority is defined using a tiering model from tier 0 (t0) for the most critical traffic to tier 5 (t5) for the least. While t0 is reserved for a small subset of critical infrastructure services, t1 represents the most important user facing online traffic, the core workloads we aim to protect during overloads. This system allows Cinnamon to shed lower-priority traffic first during overload.

With request priority awareness in place, we simplified the queue structure to just read and write queues. Long-running and background operations were marked with lower priority instead of having a separate queue.

Before Cinnamon, the CoDel queue load shedder was priority-agnostic and shedding during overload was indiscriminate.

After Cinnamon, the queue load shedder was priority-aware and shedding during overload happened in order of priority.

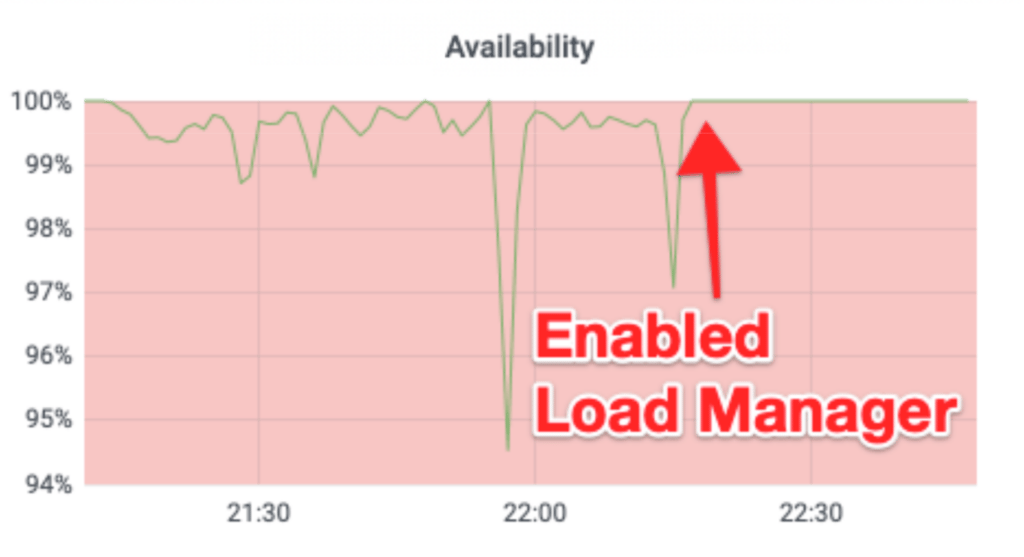

Performance and Stability Gains

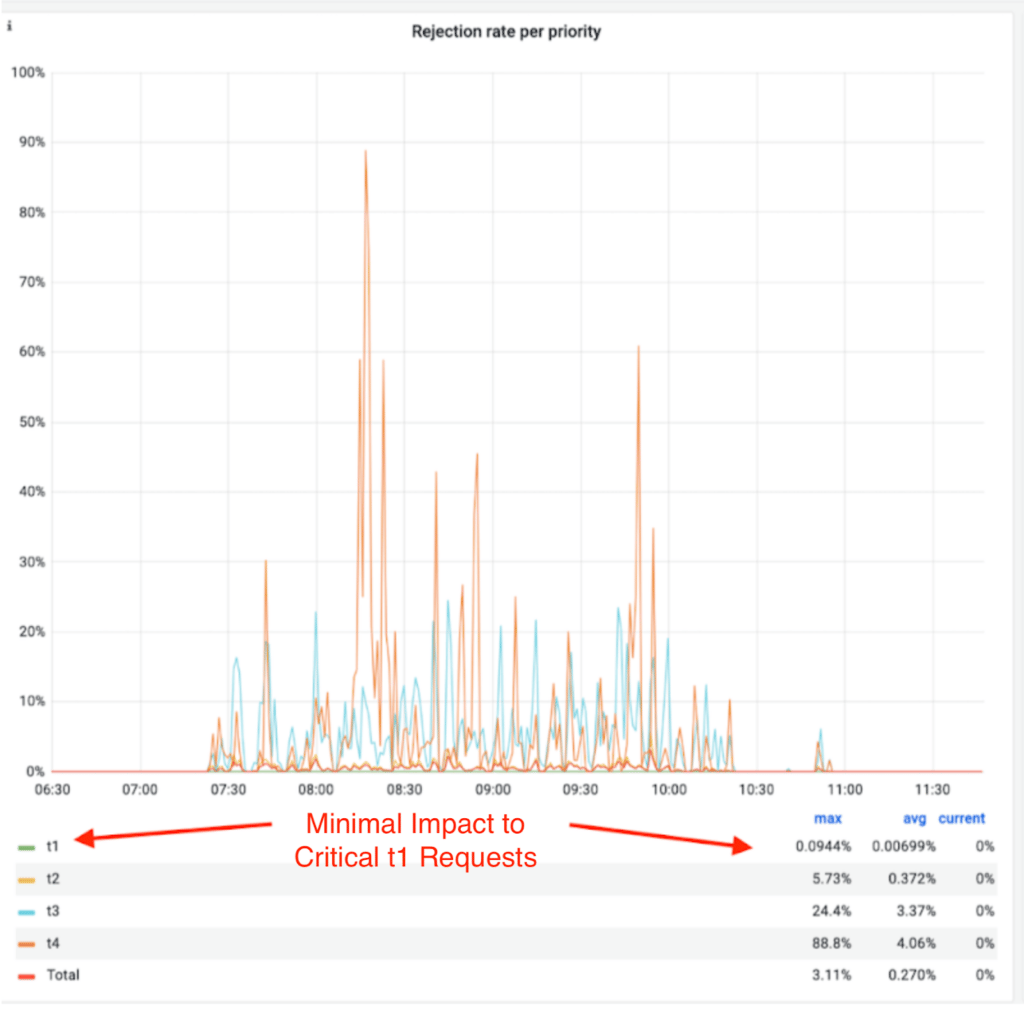

We saw performance and stability gains from the Cinnamon-based design. Requests are ranked, allowing Cinnamon to shed low-priority traffic first, protecting user facing flows. During overloads, critical user-facing requests are better protected with minimal impact.

Cinnamon also adapts queue timeout thresholds using P90 latency metrics, eliminating the need for manual tuning. Moreover, its Auto Tuner dynamically adjusts inflight limits, represented by the available slots in the blue box in Figure 10, to maximize throughput. It does this by continuously monitoring and reacting to realtime latency and error rate signals, ensuring stable and effective load shedding.

Unlike CoDel’s static approach, which aggressively rejects all requests after a fixed wait time, like 5 milliseconds, Cinnamon’s PID-based control allows the system to absorb pressure without overreacting. It dynamically adjusts queue timeouts and inflight limits based on realtime latency and error signals, shedding only when necessary. This prevents a large class of premature shedding that would otherwise lead to unnecessary rejections, retries, and thundering herd effects. The result is smoother recovery, fewer 429s, and more consistent availability without compromising system health.

Areas for Improvement

Despite the gains from Cinnamon, some key challenges remained, highlighting the need for a unified platform.

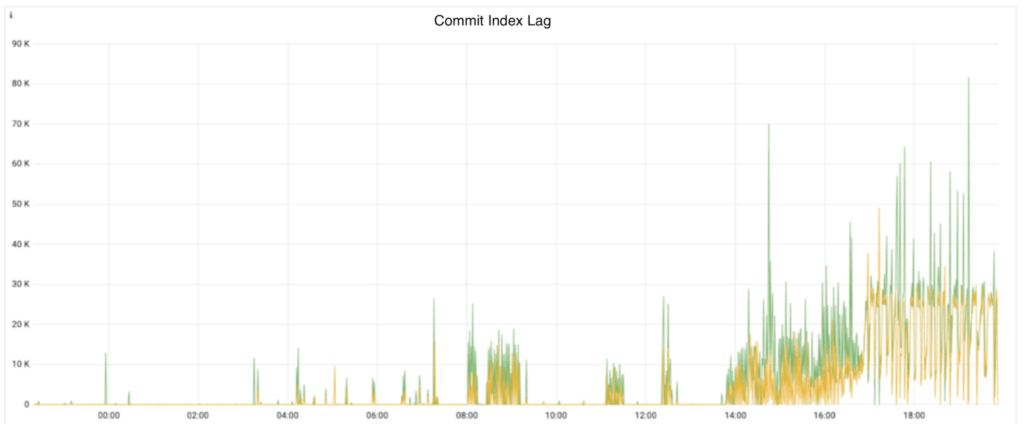

The load manager acted based on the local health of the server, tracking signals like inflight concurrency, write bytes, or memory usage. But in distributed systems, overload isn’t always local. A leader node may need to shed traffic because follower nodes are lagging, even if it’s healthy itself. We call this commit index lag. Traditionally, external components using token-bucket-based rate limiters handled such remote shedding decisions. These were easy to build but proved ineffective at scale, introducing split-brain behaviors and globally suboptimal shedding decisions.

The initial design was excellent for concurrency-based shedding, but it wasn’t built to be a reusable platform for future overload signals that would inevitably arise from a growing system.

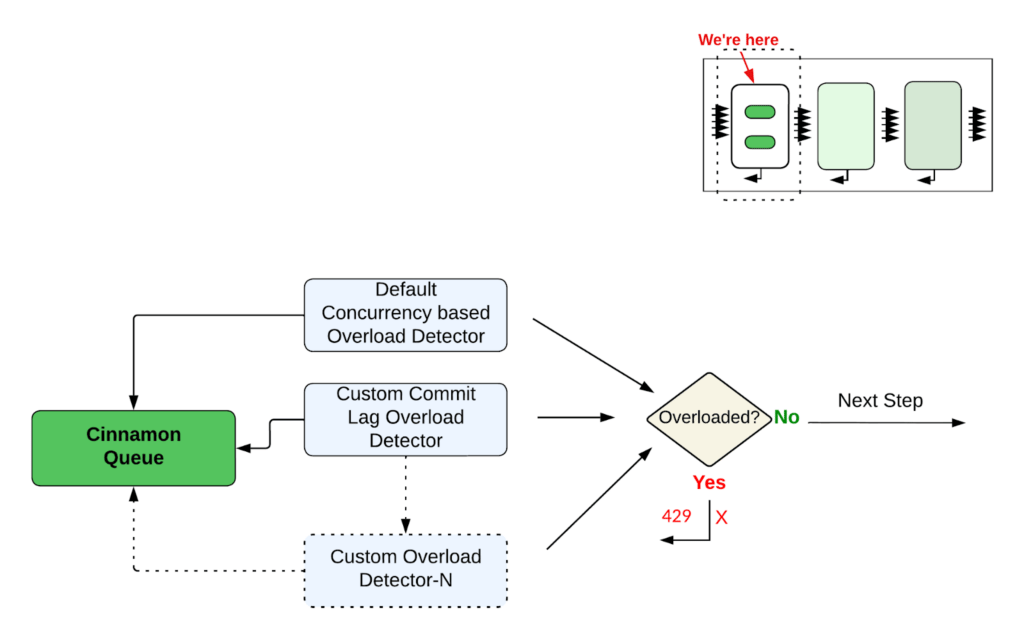

These insights led us to the final evolution of our system: transforming Cinnamon from a concurrency only shedder into a truly general purpose overload control engine. By consolidating all signals into a single, modular decision-making loop, we achieved holistic and consistent overload management.

The Unified Load Shedding Engine

Centralizing Overload Decisions

We enhanced Cinnamon to support pluggable external signals like follower commit lags, enabling the system to make globally informed, priority-aware shedding decisions within the same admission control path. This shift unified local and remote overload logic into a single control loop, closing the gaps that previously caused instability.

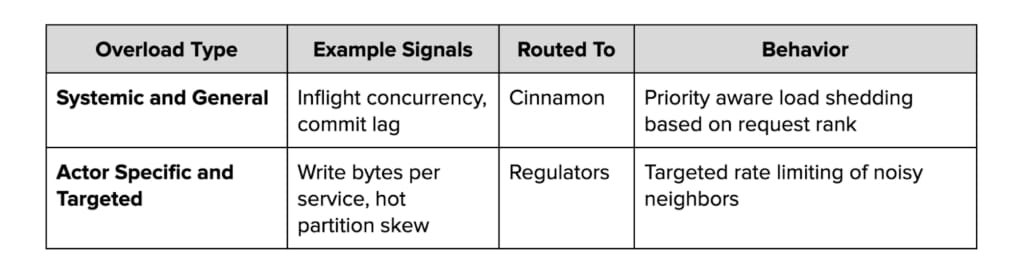

But shedding isn’t always a one-size-fits-all decision and that’s where the load manager architecture shines. Built on a BYOS (Bring Your Own Signal) ethos, it provides a pluggable framework that lets the team embed new overload signals and route them to the right control path. Whether the pressure is systemic or actor-specific, the load manager sheds broadly by priority or precisely by caller, based on the signal.

The Payoff: Unified Control, Simplified Load Management

The shift to a centralized, pluggable architecture made the system more stable and predictable, with real wins.

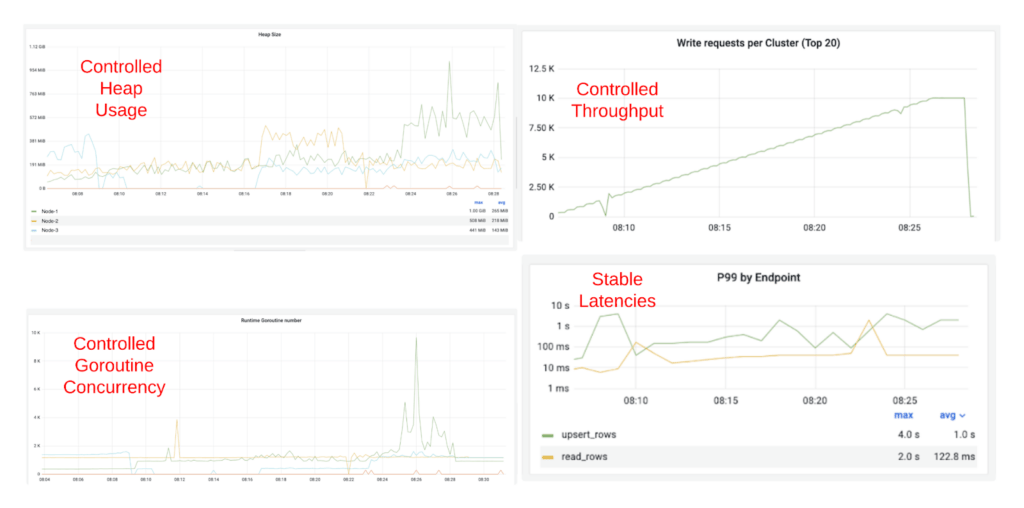

Cinnamon sheds excess requests immediately using a PID controller, avoiding the memory and goroutine buildup caused by token bucket limiters. This led to lower tail latencies and a leaner resource usage profile, even under heavy load. We saw:

- 80% increase in throughput under overload (QPS average of 5,400 versus 3,000)

- ~70% reduction in P99 latency (upsert average of 1.0 seconds versus 3.1 seconds)

- ~93% fewer goroutines during overload (peak 10,000 versus 150,000)

- ~60% lower heap usage (1 GB max versus 5-6 GB spikes)

We also saw smoother, more predictable shedding behavior. Without PID regulation, shedding acts like a hammer: reactive and abrupt. With it, it’s more like a dimmer switch: smooth and stable. The difference is clear when comparing how commit lag stabilizes under a token bucket limiter versus Cinnamon’s PID-based controller.

Lessons Learned

- Prioritization is paramount. Effective load-shedding starts with deciding what matters most. Protect critical, user-facing traffic first. Everything else is secondary.

- Fail fast, don’t block. Rejecting early is almost always better than holding requests in memory until they expire. It reduces wasted work, keeps latencies predictable, prevents OOMs, and makes the system more resilient under stress.

- PID regulation for stable shedding. Simple, reactive shedding based solely on current error rates often causes instability, overcorrecting too late, and too hard. PID based regulation brings balance by incorporating system history and directional trends, making it a critical tool for smooth, sustained, and resilient overload control.

- Place control close to the source of truth. The best shedding decisions happen where the state lives. Protection in the layer that has full context, typically the storage layer in stateful systems.

- Embrace dynamism. Avoid static configurations wherever possible. Your system should be intelligent enough to adapt to different scenarios, based on the context.

- Invest in visibility and monitoring. Good observability is the foundation for tuning and trust. Track what’s being shed, why it’s being shed, and how each component contributes to system pressure.

- Simplicity over complexity. This is a meta principle that guides all the other decisions.

Conclusion

Our journey to a resilient load manager was defined by the unique complexities of a large-scale, stateful, and distributed environment. By unifying disparate components into a single decision-making brain and adopting a Bring Your Own Signal model, we gained the flexibility to handle systemic overloads and localized noisy neighbor issues with precision. The result is a load management system that sheds smarter in a priority-aware manner, keeps tail latencies low, and drastically reduces operational toil.

If you like challenges related to distributed systems, databases, storage, and cache, apply for open positions here.

Acknowledgments

A project of this scope is rarely accomplished alone. Our sincere thanks to Rich Porter, Jesper Nielsen, Piyush Patel, and the engineers from the Storage and Delivery teams for their guidance and collaboration throughout this journey. From design reviews to on-call insights, their contributions were instrumental in building a resilient system that now safeguards some of Uber’s most critical infrastructure.

Cover Photo Attribution: “Heavy Traffic Jam in Urban City Center” by Dapur Melodi

MySQL is a registered trademark of Oracle and/or its affiliates. Other names may be trademarks of their respective owners.

Redis is a trademark of Redis Labs Ltd. Any rights therein are reserved to Redis Labs Ltd. Any use herein is for referential purposes only and does not indicate any sponsorship, endorsement or affiliation between Redis and Uber.

Dhyanam Vaidya

Dhyanam Vaidya is a Software Engineer on Uber’s Storage Platform team. He’s contributed to the design and implementation of many Docstore features. His work focuses on improving the reliability, resilience, and operational efficiency of Uber’s distributed databases at scale.

Prathamesh Deshpande

Prathamesh Deshpande is a Staff Engineer on Uber’s Storage Platform team, building database features and distributed storage systems that meet Uber’s global reliability and performance requirements. His work focuses on large-scale data management, distributed database storage systems, and platform reliability.

Mike Ma

Mike Ma is a Staff Software Engineer on Uber’s Storage Platform team, where he has contributed to multiple core components of both Schemaless and Docstore. His work focuses on scalability, reliability, performance, and operational excellence across Uber’s large scale distributed databases.

Chaitanya Yalamanchili

Chaitanya Yalamanchili is a Sr. Manager and technical lead on Uber’s Storage Platform team. He leads the development of online distributed storage systems with a focus on providing a world-class platform that powers all the critical business functions and lines of business at Uber. The platform serves tens of millions of QPS and stores tens of Petabytes of operational data.

Posted by Dhyanam Vaidya, Prathamesh Deshpande, Mike Ma, Chaitanya Yalamanchili