Uber Engineering’s Schemaless storage system powers some of the biggest services at Uber, such as Mezzanine. Schemaless is a scalable and highly available datastore on top of MySQL¹ clusters. Managing these clusters was fairly easy when we had 16 clusters. These days, we have more than 1,000 clusters containing more than 4,000 database servers, and that requires a different class of tooling.

Initially, all our clusters were managed by Puppet, a lot of ad hoc scripts, and manual operations that couldn’t scale at Uber’s pace. When we began looking for a better way to manage our increasing number of MySQL clusters, we had a few basic requirements:

- Run multiple database processes on each host

- Automate everything

- Have a single entry point to manage and monitor all clusters across all data center

The solution we came up with is a design called Schemadock. We run MySQL in Docker containers, which are managed by goal states that define cluster topologies in configuration files. Cluster topologies specify how MySQL clusters should look; for example, that there should be a Cluster A with 3 databases, and which one should be the master. Agents then apply those topologies on the individual databases. A centralized service maintains and monitors the goal state for each instance and reacts to any deviations.

Schemadock has many components, and Docker is a small but significant one. Switching to a more scalable solution has been a momentous effort, and this article explains how Docker helped us get here.

Why Docker in the first place?

Running containerized processes makes it easier to run multiple MySQL processes on the same host in different versions and configurations. It also allows us to colocate small clusters on the same hosts so that we can run the same number of clusters on fewer hosts. Finally, we can remove any dependency on Puppet and have all hosts be provisioned into the same role.

As for Docker itself, engineers build all of our stateless services in Docker now. That means that we have a lot of tooling and knowledge around Docker. Docker is by no means perfect, but it’s currently better than the alternatives.

Why not use Docker?

Alternatives to Docker include full virtualization, LXC containers, and just managing MySQL processes directly on hosts through for example Puppet. For us, choosing Docker was fairly simple since it fits into our existing infrastructure. However, if you’re not already running Docker then just doing it for MySQL is going to be a fairly big project: you need to handle image building and distribution, monitoring, upgrading Docker, log collection, networking, and much more.

All of this means that you should really only use Docker if you’re willing to invest quite a lot of resources in it. Furthermore, Docker should be treated as a piece of technology, not a solution to end all problems. At Uber we did a careful design which had Docker as one of the components in a much bigger system to manage MySQL databases. However, not all companies are at the same scale as Uber, and for them a more straightforward setup with something like Puppet or Ansible might be more appropriate.

The Schemaless MySQL Docker Image

At the base of it, our Docker image just downloads and installs Percona Server and starts mysqld—this is more or less like the existing Docker MySQL images out there. However, in between downloading and starting, a number of other things happen:

- If there is no existing data in the mounted volume, then we know we’re in a bootstrap scenario. For a master, run mysql_install_db and create some default users and tables. For a minion, initiate a data sync from backup or another node in the cluster.

- Once the container has data, mysqld will be started.

- If any data copy fails, the container will shut down again.

The role of the container is configured using environment variables. What’s interesting here is that the role only controls how the initial data is retrieved—the Docker image itself doesn’t contain any logic to set up replication topologies, status checking, etc. Since that logic changes much more frequently than MySQL itself, it makes a lot of sense to separate it.

The MySQL data directory is mounted from the host file system, which means that Docker introduces no write overhead. We do, however, bake the MySQL configuration into the image, which basically makes it immutable. While you can change the config, it will never go into effect due to the fact that we never reuse Docker containers. If a container shuts down for whatever reason, we don’t just start it again. We delete the container, create a new one from the latest image with the same parameters (or new ones if the goal state has changed), and start that one instead.

Doing it this way gives us a number of advantages:

- Configuration drift is much easier to control. It boils down to a Docker image version, which we actively monitor.

- Upgrading MySQL is a simple matter. We build a new image and then shut containers down in an orderly fashion.

- If anything breaks we just start all over. Instead of trying to patch things up, we just drop what we have and let the new container take over.

Building the image happens through the same Uber infrastructure that powers stateless services. The same infrastructure replicates images across data centers to make them available in local registries.

There’s a disadvantage of running multiple containers on the same host. Since there is no proper I/O isolation between containers, one container might use all the available I/O bandwidth, which then leaves the remaining containers starved. Docker 1.10 introduced I/O quotas, but we haven’t experimented with those yet. For now we cope with this by not oversubscribing hosts and continuously monitoring the performance of each database.

Scheduling Docker Containers and Configuring Topologies

Now that we have a Docker image that can be started and configured as either master or minion, something needs to actually start these containers and configure them into the right replication topologies. To do this, an agent runs on each database host. The agents receive goal state information for all the databases that should be running on the individual hosts. A typical goal state looks like this:

“schemadock01-mezzanine-mezzanine-us1-cluster8-db4”: {

“app_id”: “mezzanine-mezzanine-us1-cluster8-db4”,

“state”: “started”,

“data”: {

“semi_sync_repl_enabled”: false,

“name”: “mezzanine-us1-cluster8-db4”,

“master_host”: “schemadock30”,

“master_port”: 7335,

“disabled”: false,

“role”: “minion”,

“port”: 7335,

“size”: “all”

}

}

This tells us that on host schemadock01 we should be running one Mezzanine database minion on port 7335, and it should have the database running on schemadock30:7335 as master. It has size “all,” which means it’s the only database running on that host, so it should have all memory allocated to it.

How this goal state is created is a topic for another post so we’ll skip to the next steps: an agent running on the host receives it, stores it locally, and starts processing it.

The processing is actually an endless loop that runs every 30 seconds, somewhat like running Puppet every 30 seconds. The processing loop checks whether the goal state matches the actual state of the system through the following actions:

- Check whether a container is already running. If not, create one with the configuration and start it.

- Check whether the container has the right replication topology. If not, try to fix it.

- If it’s a minion but should be a master verify that it’s safe to change to master role. We do this by checking that the old master is read-only and that all GTIDs have been received and applied. Once that is the case, it’s safe to remove the link to the old master and enable writes.

- If it’s a master but should be disabled, turn on read-only mode.

- If it’s a minion but replication is not running, then set up the replication link.

- Check various MySQL parameters (read_only and super_read_only, sync_binlog, etc.) based on the role. Masters should be writeable, minions should be read_only, etc. Furthermore, we reduce the load on the minions by turning off binlog fsync and other similar parameters².

- Start or shut down any support containers, such as pt-heartbeat and pt-deadlock-logger.

Note that we very much subscribe to the idea of single-process, single-purpose containers. That way we don’t have to reconfigure running containers, and it’s much easier to control upgrades.

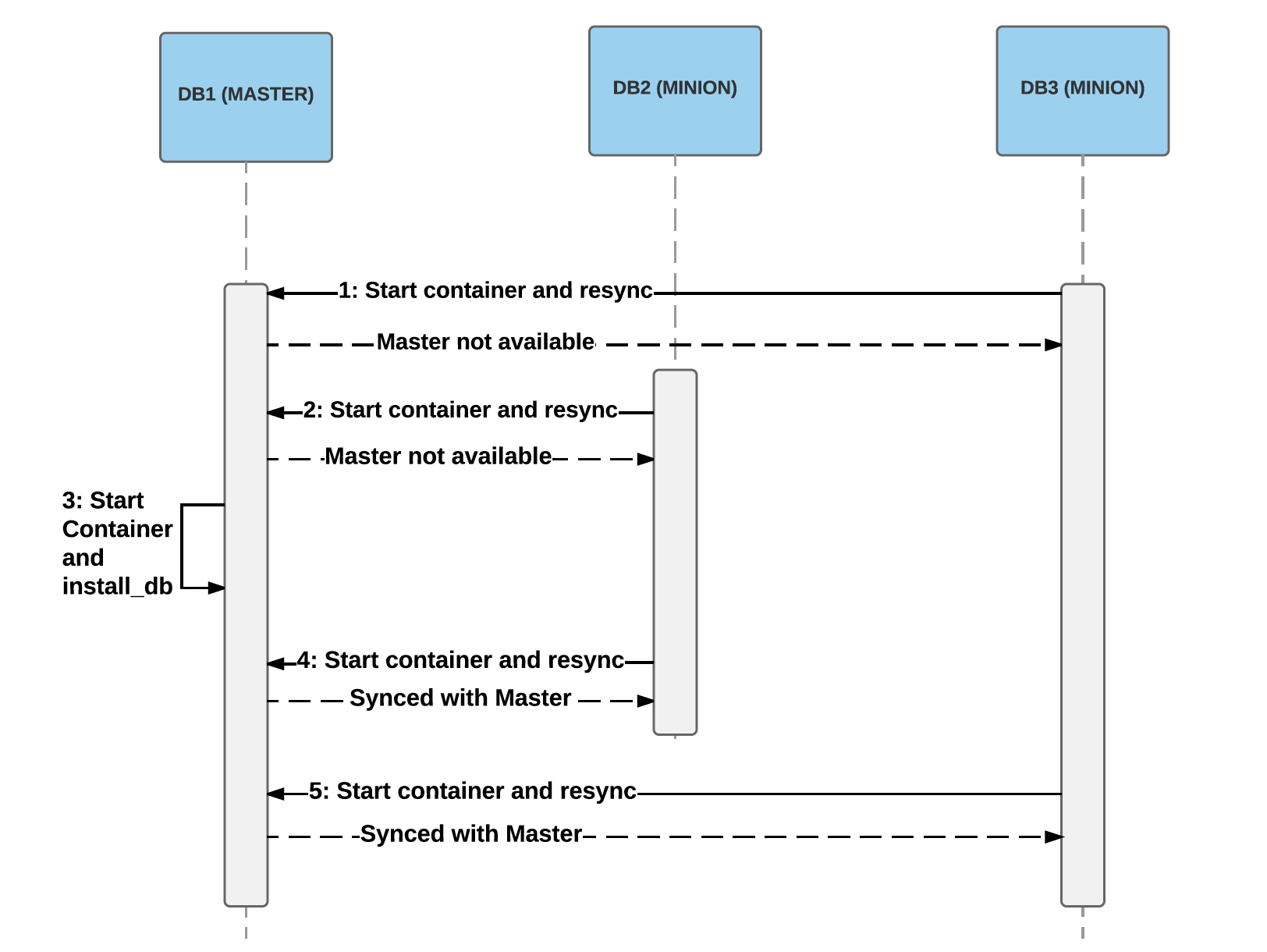

If an error happens at any point, the process just raises an error and aborts. The whole process is then retried in the next run. We make sure to have as little coordination between individual agents as possible. This means that we don’t care about ordering, for example, when provisioning a new cluster. If you’re manually provisioning a new cluster you would probably do something like this:

- Create the MySQL master and wait for it to become ready

- Create the first minion and connect it to the master

- Repeat for the remaining minion

Of course, eventually something like this has to happen. What we don’t care about is the explicit ordering, though. We’ll just create goal states reflecting the final state we want to achieve:

“schemadock01-mezzanine-cluster1-db1”: {

“data”: {

“disabled”: false,

“role”: “master”,

“port”: 7335,

“size”: “all”

}

},

“schemadock02-mezzanine-cluster1-db2”: {

“data”: {

“master_host”: “schemadock01”,

“master_port”: 7335,

“disabled”: false,

“role”: “minion”,

“port”: 7335,

“size”: “all”

}

},

“schemadock03-mezzanine-cluster1-db3”: {

“data”: {

“master_host”: “schemadock01”,

“master_port”: 7335,

“disabled”: false,

“role”: “minion”,

“port”: 7335,

“size”: “all”

}

}

This is pushed to the relevants agents in random order and they all start working on it. To reach the goal state, a number of retries might be required, depending on the ordering. Usually, the goal states are reached within a couple of retries, but some operations might actually require 100s of retries. For example, if the minions start processing first then they won’t be able to connect to the master, and they have to retry later. Since it might take a little time to get the master up and running, the minions might have to retry a lot of times:

Experience with the Docker Runtime

Most of our hosts run Docker 1.9.1 with devicemapper on LVM for storage. Using LVM for devicemapper has turned out to perform significantly better than devicemapper on loopback. devicemapper has had many issues around performance and reliability, but alternatives such as AuFS and OverlayFS have also had a lot of issues³. This means that there has been a lot of confusion in the community about the best storage option. By now, OverlayFS is gaining a lot of traction and seems to have stabilized, so we’ll be switching to that and also upgrade to Docker 1.12.1.

One of the pain points of upgrading Docker is that it requires a restart, which also restarts all containers. This means that the upgrade process has to be controlled so that we don’t have masters running when we upgrade a host. Hopefully, Docker 1.12 will be the last version where we have to care about that; 1.12 has the option to restart and upgrade the Docker daemon without restarting containers.

Each version comes with many improvements and new features while introducing a fair number of bugs and regressions. 1.12.1 seems better than previous versions, but we still face some limitations:

- docker inspect hangs sometimes after Docker has been running for a couple of days.

- Using bridge networking with userland proxy results in strange behavior around TCP connection termination. Client connections sometimes never receive an RST signal and stay open no matter what kind of timeout you configure.

- Container processes are occasionally reparented to pid 1 (init), which means that Docker loses track of them.

- We regularly see cases where the Docker daemon takes a very long time to create new containers.

Summary

We set out with a couple of requirements for storage cluster management at Uber:

- Multiple containers running on the same host

- Automation

- A single point of entry

Now, we can perform day-to-day maintenance through simple tools and a single UI, none of which require direct host access:

We can better utilize our hosts by running multiple containers on each one. We can do fleet-wide upgrades in a controlled fashion. Using Docker has gotten us here quickly. Docker has also allowed us to run a full cluster setup locally in a test environment and try out all the operational procedures.

We started the migration to Docker in the beginning of 2016, and by now we are running around 1500 Docker production servers (for MySQL only) and we have provisioned around 2300 MySQL databases.

There is much more to Schemadock, but the Docker component has been a great help to our success, allowing us to move fast and experiment while also hooking into existing Uber infrastructure. The entire trip store, which receives millions of trips every day, now runs on Dockerized MySQL databases together with other stores. Docker has, in other words, become a critical part of taking Uber trips.

Joakim Recht is a staff software engineer in Uber Engineering’s Aarhus office, and tech lead on Schemaless infrastructure automation.

Photo Credits for Header: “Humpback Whale-Megaptera novaeangliae” by Sylke Rohrlach, licensed under CC-BY 2.0. Image cropped for header dimensions and color corrected.

¹ To be precise, Percona Server 5.6

² sync_binlog = 0 and innodb_flush_log_at_trx_commit = 2

³ A small selection of issues: https://github.com/docker/docker/issues/16653, https://github.com/docker/docker/issues/15629, https://developerblog.redhat.com/2014/09/30/overview-storage-scalability-docker/, https://github.com/docker/docker/issues/12738

Joakim Recht

Joakim Recht is a Principal Engineer at Uber where he is the Tech Lead for Uber’s platform for deploying and managing stateful workloads.

Posted by Joakim Recht