How Uber Indexes Streaming Data with Pull-Based Ingestion in OpenSearch™

16 December / Global

Introduction

At Uber, our business operates in real time. Whether you’re hailing a ride, ordering from a restaurant, or tracking a delivery, search is the critical starting point. Our search platform powers these experiences at a massive scale, indexing everything from restaurant menus and destinations to the live locations of drivers and couriers.

Given its central role, our search platform must meet stringent demands for performance, scalability, and data freshness. To achieve this, its architecture was built on two foundational principles: a pull-based ingestion model and an active-active deployment. The pull-based model, built on Apache Kafka®, decouples data producers from the search cluster, allowing our platform to ingest data at its own pace for greater reliability. This is paired with an active-active architecture where we operate in multiple regions, keeping each index fresh to support seamless failovers. By consuming from Uber’s cross-replicated Kafka infrastructure, the platform maintains a consistent global view, ensuring the high availability critical to our operations.

In this blog, we’ll take you on a deep dive into the pull-based ingestion model that powers our architecture. We’ll share the journey of contributing pull-based indexing to OpenSearch and explain how this enables us to migrate our in-house search systems to the open-source platform. More details on the evolution of Uber’s search platform can be found in a prior blog.

Why Pull-Based Ingestion?

To understand why we adopted a pull-based model, it’s helpful to first examine the limitations of the push-based architecture commonly found in many search systems. In this traditional model, client applications directly send data to the search cluster via an HTTP or gRPC™ endpoint. While straightforward initially, this approach presented several challenges for complex applications operating at scale:

- Handling ingestion spikes. When traffic exceeds the server’s capacity, the cluster is forced to reject requests. This shifts the responsibility of managing backpressure and implementing complex retry logic to each client application, significantly increasing operational complexity.

- Lack of priority control. In a busy system, not all index requests are equally important. However, a standard push API offers no effective way to prioritize critical real-time updates over low-priority bulk writes. This becomes particularly problematic under heavy ingestion workloads, where important data can experience delays.

- Complex data replay. Many scenarios necessitate replaying indexing requests, such as restoring a cluster from a snapshot or performing a live migration where writes must be sent to two clusters. In a push-based model, this requires developing intricate tooling to manage the replay process, which is often manual and prone to errors.

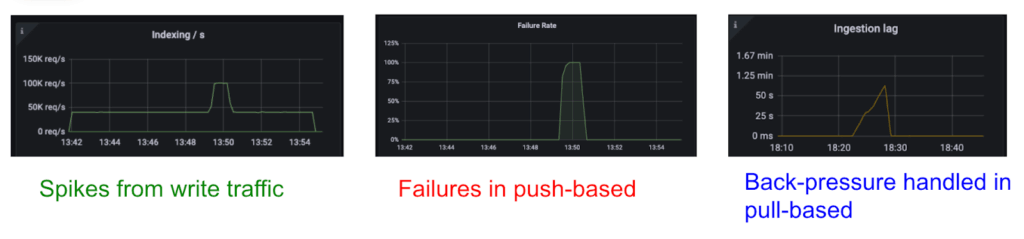

As Figure 1 shows, these challenges directly impact reliability. In a push-based system, a traffic spike leads to errors and data loss unless every client perfectly handles backpressure. Conversely, in a pull-based system, a durable buffer gracefully absorbs the same spike, resulting only in a temporary lag that is eventually caught up without any errors.

For OpenSearch specifically, the translog ensures the durability of uncommitted index changes. However, under heavy ingestion, the translog can grow excessively, risking overflow and causing instability. In document-replication mode, the system must await synchronous replication to complete on other nodes, adding latency to each request. Neither the translog nor synchronous replication is strictly necessary in a streaming ingestion model. A durable streaming buffer like Kafka can provide more efficient durability, allowing the cluster to focus on indexing. For these reasons, building a native, pull-based ingestion framework for OpenSearch became a critical step for our adoption.

Pull-Based Ingestion in OpenSearch

To address the challenges of push-based indexing, we developed and contributed a native pull-based ingestion framework to the OpenSearch project. This feature, available as an experimental release starting in OpenSearch 3.0, provides a more resilient and controllable method for stream-based indexing. In this section, we detail its core architecture and end-to-end data flow. Documentation can be found on the OpenSearch website.

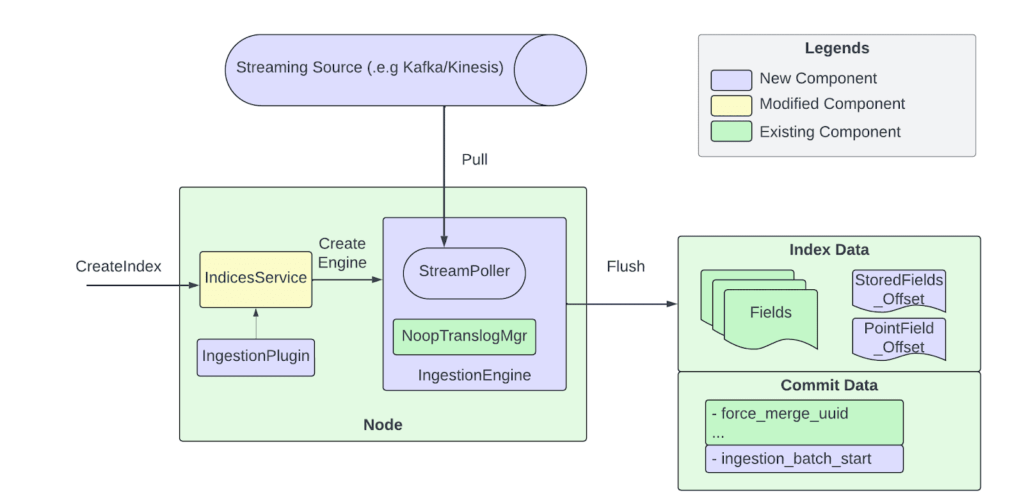

The contribution to pull-based ingestion in OpenSearch adds several new components and extends core OpenSearch modules to support native stream consumption. The architecture, shown in Figure 2, centers around a new IngestionPlugin interface that enables integration with streaming platforms. Currently, we support two plugins: ingestion-kafka and ingestion-kinesis. We introduced a StreamPoller component to handle source-specific consumer logic for pulling data from Kafka partitions or Amazon Kinesis™ shards. In this model, each OpenSearch shard maps to a corresponding stream partition. During index creation, as OpenSearch initializes each shard, the associated stream consumer and a specialized IngestionEngine are also initialized to manage ingestion for that shard.

In streaming ingestion mode, the traditional durability guarantees provided by the translog are no longer necessary. Instead, durability is offloaded to the underlying streaming platform, which inherently persists messages. The IngestionEngine replaces the traditional translog with a no-op translog manager, eliminating the overhead of maintaining a write-ahead log for streamed data. This simplification not only reduces I/O and storage pressure under high ingestion rates but also aligns with the design principle of using the stream itself as the source of truth. By relying on durable, replayable streams, OpenSearch can safely discard the translog without compromising data durability.

Data Flow

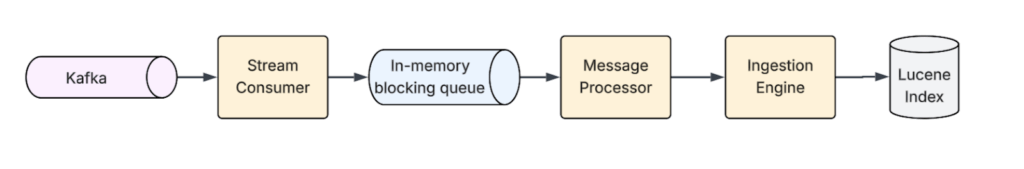

OpenSearch’s pull-based ingestion comprises multiple components. Figure 3 shows their interactions and the end-to-end flow a message follows before it is indexed into Apache Lucene™.

The streaming ingestion components operate as follows:

- Streaming source. Events to be consumed by the OpenSearch cluster get produced into a Kafka or Kinesis topic. Streaming sources are durable, and allow replaying of events to support shard recovery. OpenSearch shards and Kafka partitions/Kinesis shards follow a one-to-one static mapping, with shard 0 consuming from partition 0, shard 1 consuming from partition 1, and so on.

- Stream Consumer. A consumer pulls new messages from the streaming source on each primary shard. Messages are then written into a blocking queue. In case the blocking queue is full, the poller waits for it to free up before reading the next set of messages from the streaming source. One consumer is initialized for every streaming source configured.

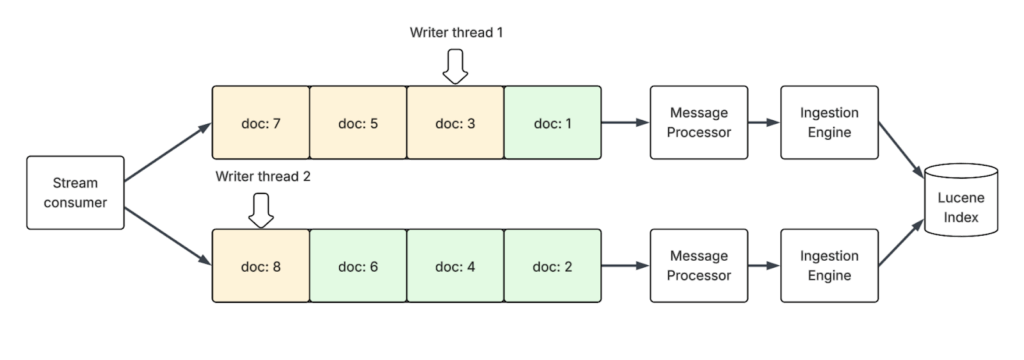

- Blocking queue. Polled messages are written to an in-memory blocking queue. This decouples the consumer and processor to improve throughput. The blocking queue can optionally be partitioned by document ID, with each partition having its own writer thread. Increasing partition count helps parallelize writes to improve ingestion throughput.

- Message Processor. The processor, running on its own thread separate from the consumer, validates, processes, and transforms the messages into indexing requests. These are then handed over to the engine.

- Ingestion Engine. The ingestion engine is responsible for processing indexing requests to add, update, and delete documents from the Lucene index. This engine maintains a no-op translog, bypassing traditional push-based ingestion flows. The most recently processed message pointer (Kafka offset or Kinesis sequence number) is included along with every commit to support recovery flows.

Shard Recovery

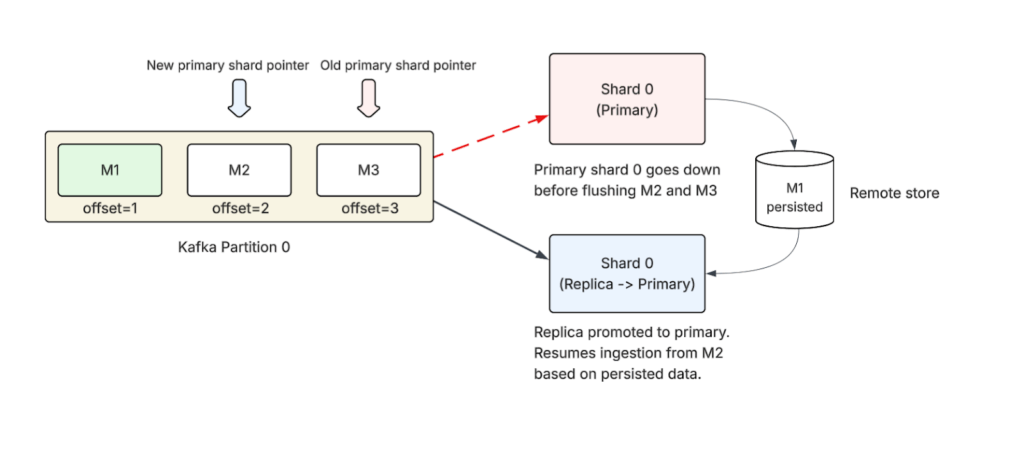

One of the central architectural choices in pull-based ingestion is eliminating the translog. Instead of maintaining a local write-ahead log for durability, the system treats the streaming source (like Apache Kafka) as the durable source of truth. This removes translog I/O from the hot path, and lowers cluster write overhead. But, it requires a resilient shard-recovery mechanism.

This recovery process is built on the following key metadata: the BatchStartPointer. This is a checkpoint stored with every commit. It represents the minimum offset that’s currently being processed across all active writer threads for that shard. This is the ingestion starting point for shard recovery.

When a primary shard fails and one of its replicas is promoted to the new primary, the following recovery sequence is triggered to ensure no data is lost and no duplicates are created:

- Initialization. The newly promoted primary shard initializes its Ingestion Engine.

- Retrieve safe checkpoint. The engine reads the last successful commit data to find the last known batchStartPointer.

- Rewind the consumer. The engine instructs the stream consumer (the Kafka consumer) to rewind and begin fetching messages starting from the batchStartPointer offset.

- Replay and index. The consumer starts pulling messages from the identified batchStartPointer to recover lost documents during the crash.

Let’s look at an example to illustrate how the batchStartPointer ensures consistency across multiple writer threads.

Imagine a stream of Kafka messages for documents 1 through 8. These messages are distributed into a blocking queue with two partitions based on the document ID—odd-numbered documents go to one, and even-numbered to the other (document ID % 2 partitioning). Two writer threads consume from these queues and index documents independently.

Because the threads run at different paces, it’s possible that writer thread 1 has only processed document 1, while the faster writer thread 2 has already processed documents 2, 4, and 6. If the shard fails at this moment, the system can’t simply resume from the last known offset (6), as it’d miss the documents that writer thread 1 has yet to process.

Instead, each writer thread tracks its progress. When a new commit is created, the IngestionEngine consults all writer threads and takes the minimum of their last successfully processed offsets. In this case, the minimum offset is 1 (from writer thread 1). This value is stored with the commit as the batchStartPointer. During recovery, the shard uses this safe checkpoint to resume ingestion, ensuring that all messages after offset 1 are processed while skipping any that are already indexed based on document-level versioning.

Controlling the Flow: Versioning, Error Handling, and Ingestion Management

Beyond its core architecture, pull-based ingestion includes several essential features designed to handle the complexities of real-world data streams. These built-in controls allow operators to manage out-of-order data, handle processing failures, and exert fine-grained control over the ingestion pipeline.

Messages aren’t always guaranteed to arrive in the exact order they were generated. Network latency, producer retry logic, or cross-region replication can all lead to out-of-order events. If not handled correctly, an older update could overwrite a newer one, leading to data inconsistency. Pull-based ingestion supports external versioning to handle these cases. The user controls the document versioning and has the option to set a version in every message. Pull-based ingestion’s at least once processing guarantee along with versioning also ensures consistent view of documents.

Operators can also handle processing failures. Failures can occur due to schema mismatches or other processing issues. Pull-based ingestion provides two configurable policies to let you decide how the system should react to such failures.

- Drop policy. If a message fails to be processed, it’s discarded, and the consumer moves on to the next message. This is the recommended policy for pull-based ingestion in OpenSearch, as only full-document upserts are supported today. The subsequent version being processed should provide the latest state of the document.

- Block policy. If a message fails, the consumer retries it indefinitely, effectively blocking that specific source partition until the message can be processed successfully. This policy is designed for use cases where every message must be accounted for and message loss is unacceptable for a given document.

Finally, a suite of dedicated APIs provides direct operational control over the ingestion process. Operators can use these endpoints to pause and resume ingestion on demand for a given index, or even reset the consumer to a specific offset in the stream. The ability to reset is particularly powerful for skipping a large backlog of messages after a prolonged outage, allowing a system to catch up to real-time processing more quickly.

Ingestion Modes

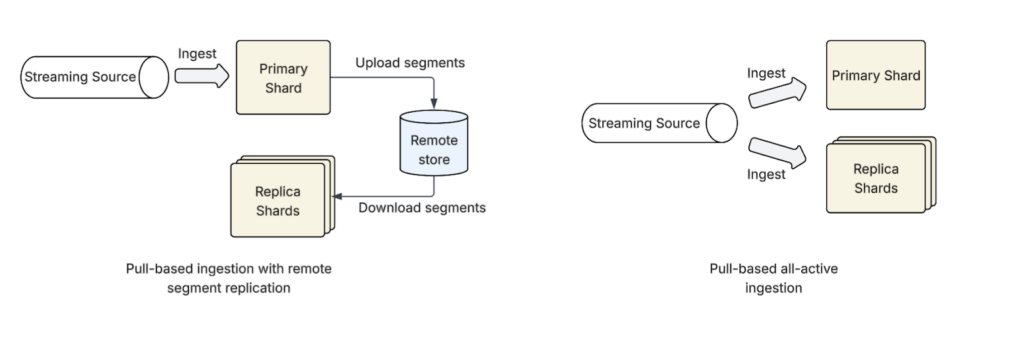

Pull-based ingestion offers two distinct operational modes for how data is indexed and replicated across shards: the default segment replication mode and an all-active ingestion mode.

In the standard segment replication mode, only the primary shard actively ingests and indexes data from the streaming source. As the primary shard creates new Lucene segments, these segments are copied to its replicas. For optimal performance and scalability, it’s highly recommended to use a remote store to facilitate this replication.

This approach is highly efficient, as the computationally expensive work of indexing is performed only once on the primary shard. Replica shards simply download the completed segments, conserving CPU resources. However, there’s a slight replication lag, meaning data indexed on the primary shard takes a short time to become visible on its replicas.

In the all-active mode, every shard copy (both primary and replica) connects to and ingests from the same streaming source independently. Each shard builds its own local index segments from the stream, with no replication or coordination between them. This model is analogous to traditional document replication, where each shard copy performs its own indexing work.

Because all shards ingest in parallel, there’s virtually no replication delay. As soon as a document is indexed, it becomes visible across all copies simultaneously (assuming no ingestion lag from the source). Additionally, unlike push-based document replication mode, scaling replicas doesn’t impact throughput. However, this mode consumes more compute resources across the cluster, as every replica duplicates the indexing work performed by the primary. This is similar to the push-based document replication mode.

OpenSearch Pull-Based Ingestion at Uber

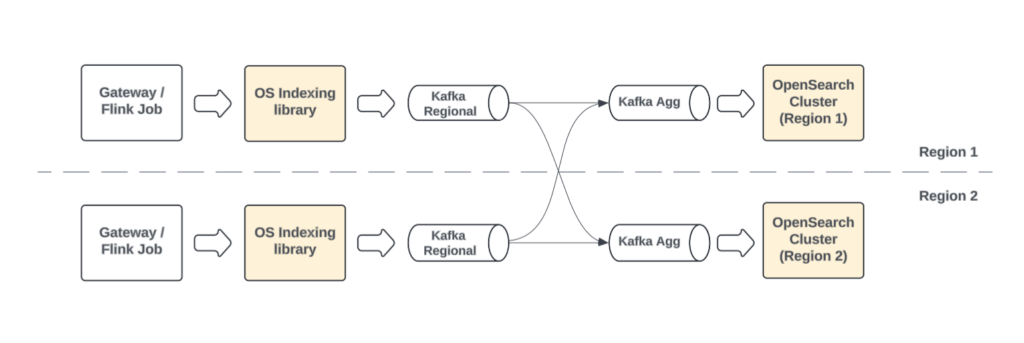

The pull-based ingestion model is a requirement for Uber’s highly available, multi-region search architecture. For business continuity, our search platform operates across multiple geographic regions, with each deployment needing a fresh, complete view of our global data.

Our data pipeline is designed for this architecture. The search platform gateway service (or Apache Flink® jobs) preprocesses and validates the incoming data against a schema before writing to their local, regional Kafka topics. From there, Uber’s foundational Kafka infrastructure handles cross-region replication, consolidating these regional streams into global aggregated topics.

This is where pull-based ingestion becomes critical. In each region, our OpenSearch clusters independently consume from these aggregated Kafka topics. By pulling from the same consistent, global source, each cluster can build a complete and up-to-date index. This architecture provides two key benefits: redundancy and global consistency. Each regional cluster contains a full copy of the data, enabling seamless failover in the event of an outage. And, all users, regardless of which region is serving their request, interact with a consistent, global view of the data.

This setup allows us to fully leverage the resilience of both our Kafka infrastructure and the pull-based model to deliver a search experience that’s highly available and globally coherent.

Conclusion

We’ve already begun migrating existing small-scale use cases to OpenSearch’s pull-based ingestion model. Our vision for the future is twofold: expanding this migration and continuing to enhance the core capabilities of the platform.

Our long-term goal is to move all search use cases to this model as part of a broader strategic shift towards a Cloud-Native OpenSearch using pull-based ingestion. This next-generation architecture, which we’re actively working on, is built on a shared-nothing design where nodes operate independently and use native cloud services for storage and compute. By embracing this cloud-native approach, we aim to achieve greater scalability, improved operational efficiency, and enhanced resilience for modern, data-intensive applications.

We’re excited to continue this journey of building with, collaborating on, and contributing back to the OpenSearch community. As part of this effort, we plan to keep enhancing pull-based ingestion with powerful features like concurrent pollers for higher throughput and priority-aware ingestion to support even more advanced use cases.

Cover Photo Attribution: “Stream Dreams | Talakona“ by VinothChandar is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Amazon Web Services®, AWS®, Amazon Kinesis, and the Powered by AWS logo are trademarks of Amazon.com, Inc. or its affiliates.

Apache®, Apache Lucene Core™, Apache Spark™, Flink®, Apache Kafka®, and the star logo are either registered trademarks or trademarks of the Apache Software Foundation in the United States and/or other countries. No endorsement by The Apache Software Foundation is implied by the use of these marks.

gRPC is a trademark of The Linux Foundation.

OpenSearch™ is a trademark of LF Projects, LLC.

Stay up to date with the latest from Uber Engineering—follow us on LinkedIn for our newest blog posts and insights.

Yupeng Fu

Yupeng Fu is a Principal Software Engineer on Uber’s SSD (Storage, Search, and Data) team, building scalable, reliable, and performant online data platforms. Yupeng is a maintainer of the OpenSearch project and a member of the OpenSearch Software Foundation TSC (Technical Steering Committee).

Varun Bharadwaj

Varun Bharadwaj is a Software Engineer on Uber’s Search Platform team, building scalable and performant solutions powering Uber’s search capabilities. He’s an OpenSearch project maintainer and also a contributor of the pull-based ingestion feature in OpenSearch.

Shuyi Zhang

Shuyi Zhang is an Engineering Manager at Uber leading OpenSearch adoption and development at Uber and innovations in open source. She’s also a member of the Observability technical advisory group under the OpenSearch project.

Xu Xiong

Xu Xiong is a Software Engineer on Uber’s Search Platform team, focusing on building and scaling the search platform. He’s also a contributor to the pull-based ingestion feature in OpenSearch.

Michael Froh

Michael Froh is a Software Engineer on Uber’s Search Platform team. He is an OpenSearch project maintainer and an Apache Lucene committer. He’s also a member of the OpenSearch Software Foundation TSC (Technical Steering Committee).

Posted by Yupeng Fu, Varun Bharadwaj, Shuyi Zhang, Xu Xiong, Michael Froh