Powering Billion-Scale Vector Search with OpenSearch

December 18, 2025 / Global

Introduction

At Uber, our systems handle massive amounts of data daily, from ridesharing to delivery. We’ve traditionally used keyword-based search with Apache Lucene™. However, we needed to move beyond simple keyword matching to semantic search to understand the meaning behind searches.

To achieve this, we adopted Amazon® OpenSearch as our vector search engine. Its scalability, performance, and flexibility were key factors in our decision. This blog post explores our journey of evaluating and implementing OpenSearch for large-scale vector search, focusing specifically on the infrastructure challenges and solutions we encountered.

Why OpenSearch?

Our infrastructure for semantic search began with Apache Lucene and its HNSW (Hierarchical Navigable Small World) algorithm. We were initially excited about the prospect of incorporating vector embeddings from our machine learning models to power semantic retrieval. Early prototypes demonstrated the potential to significantly improve user experiences.

However, as our use cases expanded and our data grew, we met several roadblocks with Lucene’s HNSW approach. We found ourselves limited by the lack of algorithm options, which hindered our ability to fine-tune tradeoffs for different scenarios. This meant we couldn’t always provide our users with the most accurate results or cost-efficient options. Furthermore, the absence of native GPU support became a performance bottleneck when dealing with the high-dimensional vectors required for complex tasks like personalized recommendations and fraud detection. This led to slower response times and limited the potential capabilities of the machine learning models we could deploy.

To overcome these challenges, we evaluated other solutions, including Milvus and OpenSearch. OpenSearch quickly emerged as the ideal platform. Unlike Lucene, OpenSearch offers various ANN algorithms, allowing us to choose the best approach for each use case. Several considerations guided this decision:

- Flexibility in vector algorithms. Unlike Lucene, OpenSearch offers various ANN (approximate nearest neighbor) algorithms, allowing us to choose the best approach for each use case and optimize for different search requirements.

- Future GPU acceleration. Its native integration with Meta® FAISS (Facebook AI Similarity Search) opens up exciting possibilities for GPU acceleration, promising significant performance improvements and allowing us to leverage more sophisticated machine learning models.

- Scalability and versatility. OpenSearch’s robust features and APIs provide the scalability and versatility needed to handle our diverse search needs and ensure a smooth and responsive user experience.

Our decision to adopt OpenSearch goes beyond simply selecting the best technology for our needs. It also marks the beginning of a strategic partnership with Amazon and a deeper engagement with the open-source community.

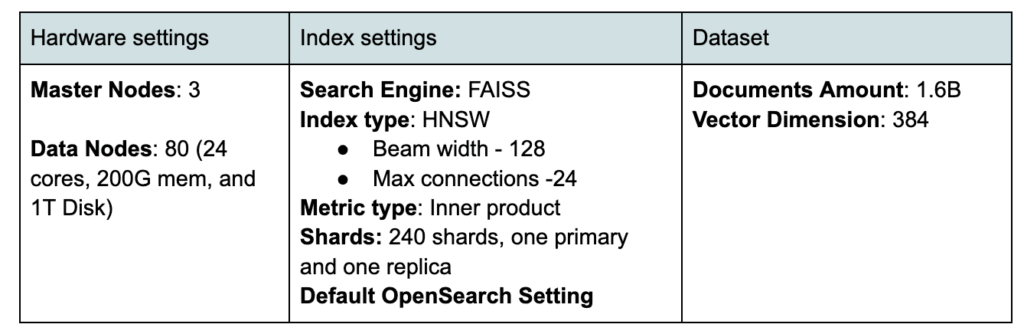

Use Case

To truly showcase the power of OpenSearch for vector search, we’ll delve into a large-scale prototype we developed in 2024. This prototype tackles the challenge of searching through a massive dataset of over 1.5 billion items, enabling users to quickly and easily find what they’re looking for within the Uber ecosystem. Each document in this data represents an item with rich information, such as name and price. We embed each document with a vector with nearly 400 dimensions to enable semantic retrieval.

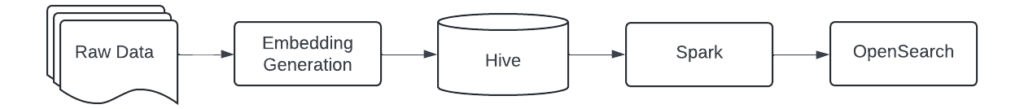

We heavily rely on batch ingestion to feed data into OpenSearch. The workflow for this prototype is fairly straightforward:

- Embedding generation. Raw data is processed and transformed into Apache Hive™ for indexing.

- Ingestion and indexing. Processed data and embedding are ingested into OpenSearch in batches using Apache Spark™ and the efficient bulk indexing API.

- Search. We leverage OpenSearch and FAISS for queries.

Challenges

Supporting this scale and ensuring low latency wasn’t without its hurdles. We had to overcome significant challenges related to ingestion speed, query performance, and stable performance during ingestion.

Ingestion Speed

Building billion-level vector data indices is a highly compute-intensive and time-consuming task. We couldn’t efficiently utilize our compute and I/O resources with default settings. This led to over 10 hours of building a base index. This inefficiency could significantly hinder business development and slow down the pace of iterations for vector search-driven applications.

We set up the baseline using the default settings, and it took 12.5 hours to ingest the whole dataset.

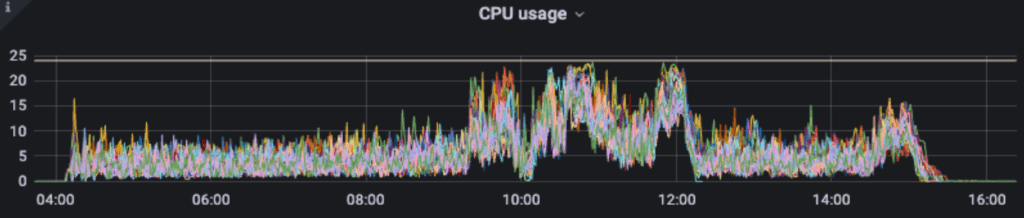

We noticed that the baseline indexing job underutilized the available CPU resources, often tapping into less than half of the allocated capacity, as shown in Figure 3. Given that building the HNSW vector search index is a CPU-heavy task, improving CPU utilization promised a significant performance boost in the indexing process.

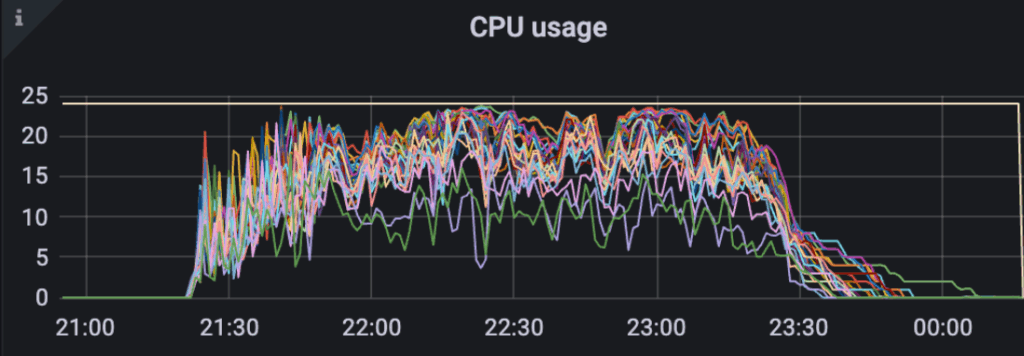

To increase CPU utilization, as shown in Figure 4, we increased our indexing job throughput. We developed a Spark-based batch ingestion tool powered by the open-source Spark OpenSearch connector. To boost indexing throughput, we ramped up the number of Spark cores, executors, and partitions. We also increased the number of threads (knn.algo_param.index_thread_qty) for native KNN index creation.

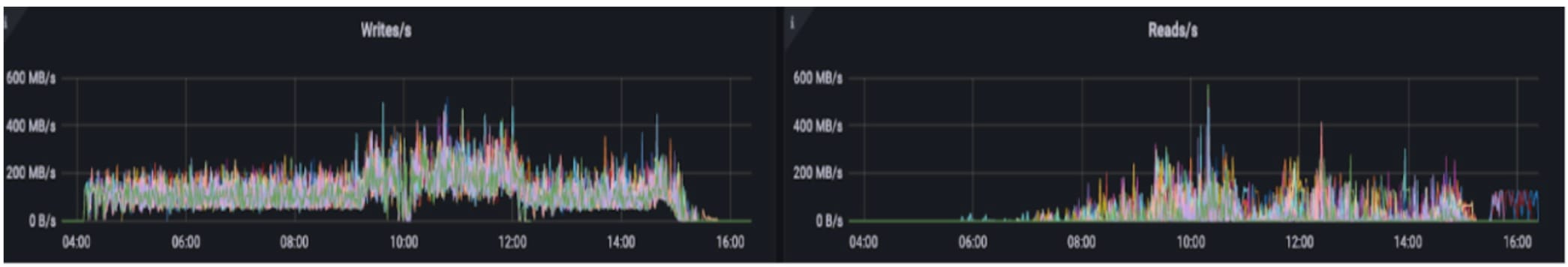

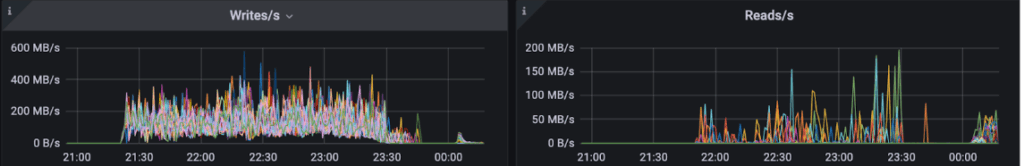

Metrics indicated that the baseline indexing process drove excessive read/write I/O, as shown in Figure 5. This high I/O usage likely contributed to delays in indexing documents. The total I/O volume even surpassed the size of the index itself, suggesting unnecessary redundant writes. The elevated read I/O further pointed to frequent background segment compaction. These issues were likely due to the generation of numerous small segments during the indexing process. Frequent refreshes and flushes, combined with an inadequate merge policy, likely caused the proliferation of these small segments.

To mitigate the impact of disk I/O amplification, we took several steps to reduce unnecessary read disk I/O, as shown in Figure 6. First, we reduced the refresh operation. We disabled the default one-second refresh interval and refreshed only with each index request (index.refresh_interval:-1). Then, we updated the flush policy to reduce flush operations. We increased the flush_threshold_size from 518 MB to 1,024 MB. We also changed the flush behavior from a per-index request to a sync per 120 seconds. To update the merge policy, we increased the initial segment size from 1m to 10m, reducing the small segment files. We also reduced merging frequency by increasing segments_per_tier from 10 to 15 and max_merge_at_once from 10 to 15. This reduced the chance of triggering the merge operation.

We disabled _source and doc_values in the index settings to reduce the index size from 11 TB to 4 TB, alleviating I/O and disk pressure.

Query Performance

At Uber, we usually have a relatively strict latency requirement to ensure a smooth experience for our customers, including search. Typically, we target a 100 ms P99 latency at 2K QPS. To meet this requirement, we faced several challenges with scalability and diverse tuning points. For scalability, we had no predecessor of tuning an OpenSearch cluster to serve a billion-scale KNN index to learn from, especially when with a strict latency requirement from our use cases. For diverse tuning points, there were a few dozens of tunable configurations, at the cluster level and index level, that could impact query performance. It was difficult to systematically understand the direction and scale of their impact, especially when combined.

Our initial setup, using the unchanged cluster/index configuration after ingestion, could serve with a P99 latency of 250 ms at 2K QPS.

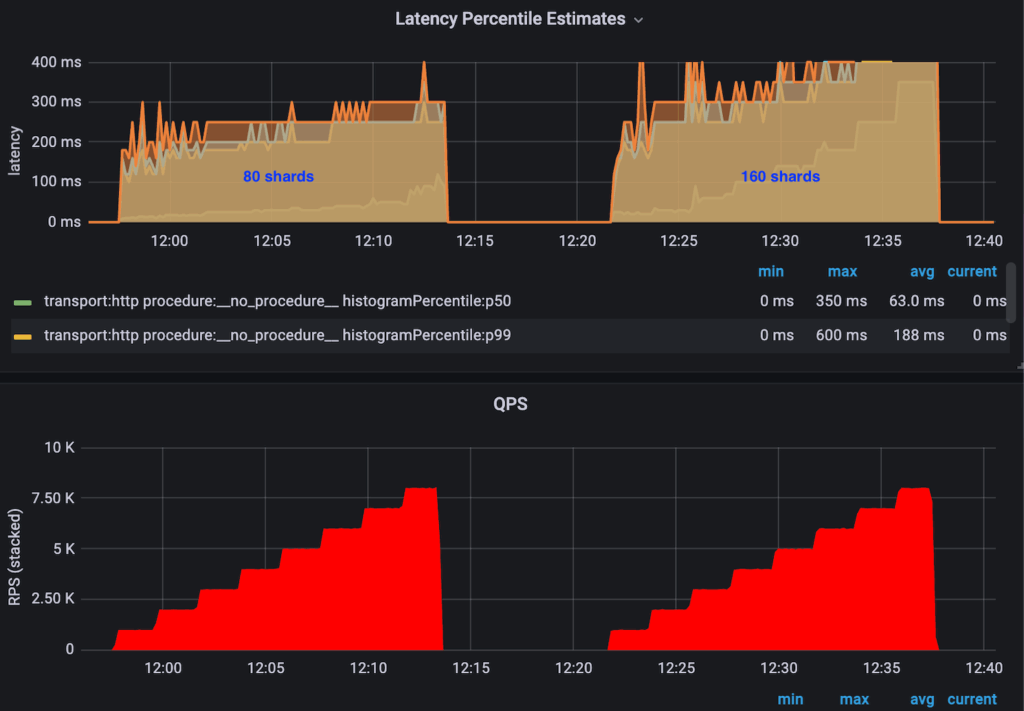

When the shard count is smaller than the node count in the cluster, more shards usually mean more parallelism in processing queries, which generally translates to lower latency. When the shard count is larger than the node count, the node count bounds parallelism. Instead, the overhead in aggregating results from different shards might outweigh the gains and impact query performance negatively.

We observed the best performance when the shard count equaled the node count for this specific use case, as shown in Figure 7.

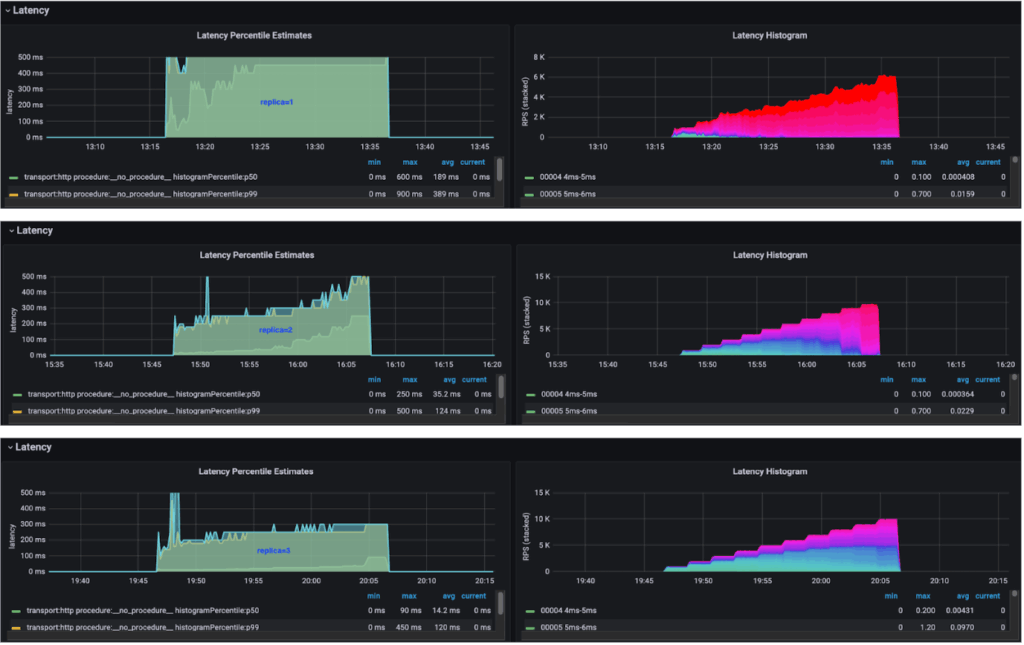

In our use case, the fanout query workload was distributed across all the shards, and all the nodes. Without replicas, the slowest node in the cluster always bounded latency. Adding replicas could further smooth this out. So, more load could be allocated to nodes with better performance, like better host network conditions or quieter neighbors. In theory, this could provide better overall performance.

Combined with the baseline numbers, we saw a clear trend of the more the replica count, the better the overall query performance, which aligned with our theory.

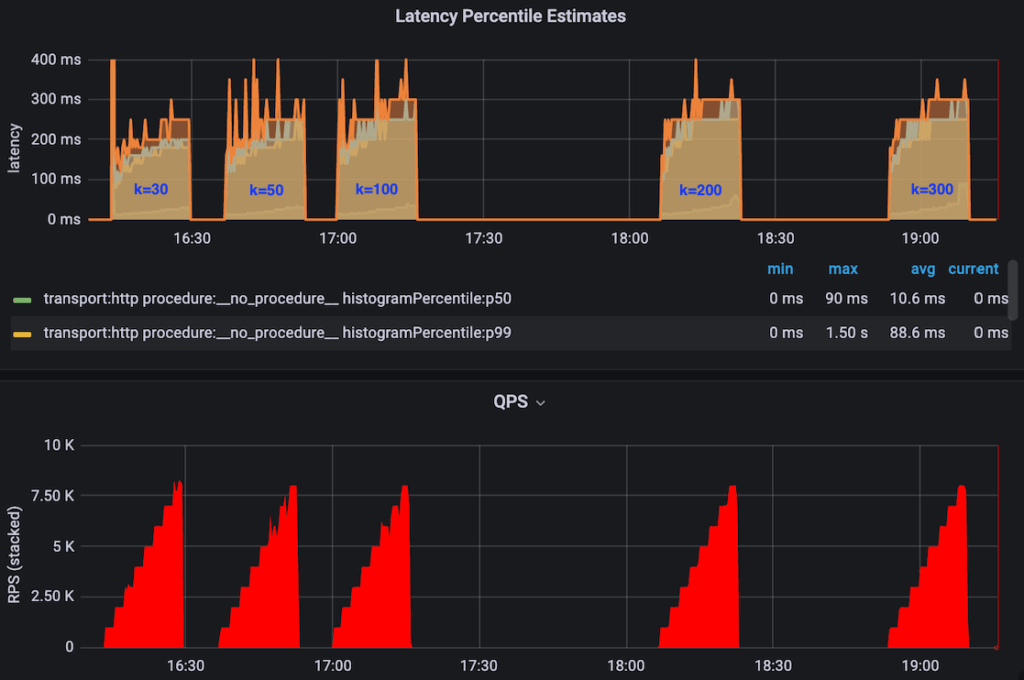

The larger the K was, the better the overall data quality was after subsequent rankers, but at the cost of worsening the query performance. We always wanted higher recall, but we needed to understand the impact of a larger K.

We saw clearly that the higher K was, the higher the overall latency was. However, it was only by a small margin, as shown in Figure 9.

Graph traversal was efficient only when loaded into memory entirely. Without this, we’d have needed extensive disk IO during query time, significantly impacting performance. Two variables controlled the memory allocated for hosting the KNN graph: the total memory allocation for the data node and the knn.memory.circuit_breaker.limit configuration, which controls the percentage of memory allocated for hosting the KNN graph after excluding the JVM heap memory.

When the allocated memory was smaller than the KNN graph (for example, knn.circuit_breaker.triggered=true), the query time was in the range of tens of seconds. We observed extensive disk IO when executing queries, especially for fan-out queries that reached every shard.

CSS enables concurrent search on multiple segments on multiple cores. It should’ve, in theory, reduced query latency under certain conditions.

We did observe high CPU usage when CSS was enabled. However, the compute resource was exhausted much earlier for the same reason, resulting in a lower saturated QPS, from 10K to 7K. Further, for this specific case, we didn’t observe an obvious gain of P99 latency at 2K QPS, likely due to the search space already being small, so the overhead of CSS might’ve outweighed the gain. We did observe noticeable gains in some other use cases where:

- Search space was large (larger shards or more relaxed filters)

- Compute cores were underutilized

- Had more than one segment per shard

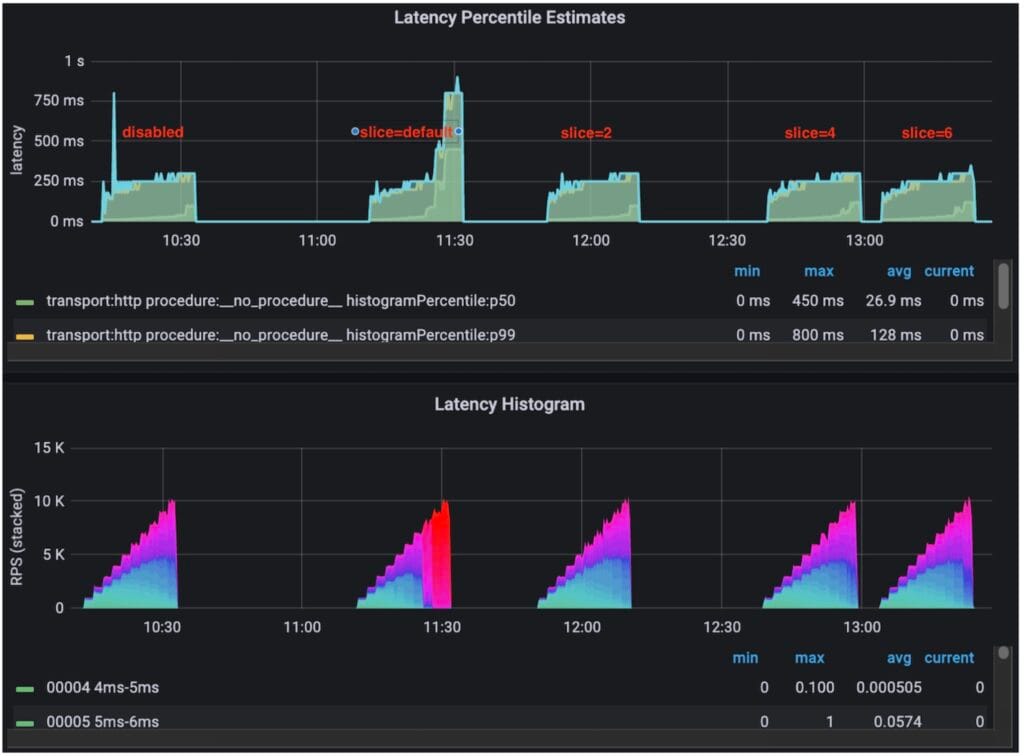

Stable Latency During Ingestion

As our vector search-driven use case rapidly scales, regularly creating new base indices becomes essential. However, generating indices for billions of vectors requires intensive resources, which can heavily strain search performance when the new index is built within the same cluster.

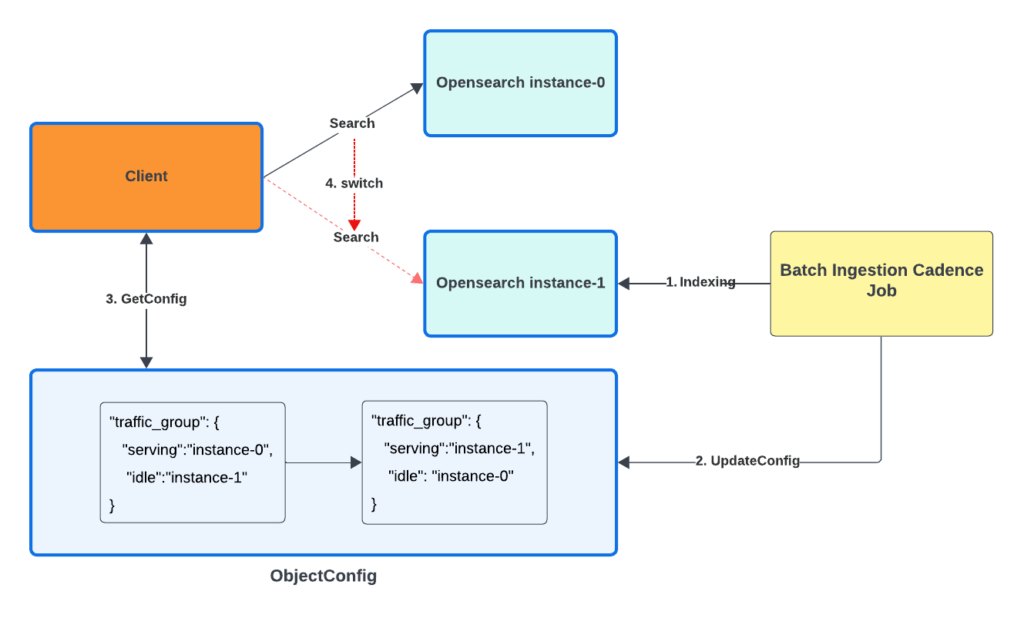

We implemented blue/green deployments by creating a new index on a separate cluster and smoothly rerouting traffic, guaranteeing zero downtime and minimal disruption to search performance. Figure 11 shows the high-level architecture.

Performance Summary

To summarize our optimization efforts, we significantly boosted performance by improving both indexing and query processes:

- Indexing. Reduced ingestion time from 12 hours to 2.5 hours through optimized bulk indexing, CPU, memory, Spark, and OpenSearch configuration tuning. That’s over 79% faster!

- Querying. Decreased p99 latency from 250 ms to under 120 ms by optimization, which represents a 52% reduction in latency.

These improvements show OpenSearch’s ability to handle massive vector search workloads efficiently. This sets the stage for even more ambitious projects. We’ll continue fine-tuning our system to achieve optimal performance as we scale and evolve our search capabilities.

Future Work

Our journey with OpenSearch is just beginning. We’re excited to continue exploring its capabilities and further improve our vector search system.

One area of future work will be in enhancing vector search performance with GPU. Leveraging GPU acceleration has the potential to significantly boost the performance of our vector engine, especially as our dataset continues to grow. This will translate to faster search results, improved responsiveness, and a better overall experience for our users. The OpenSearch community has proposed a plan to enable GPU acceleration, and Uber plans to contribute to these efforts. By harnessing the power of GPUs, we aim to amplify the performance of the OpenSearch vector engine, especially when dealing with massive datasets.

Another area for future work is separating indexing and search traffic within a cluster to achieve independent scalability and failure/workload isolation, especially on a massive-scale dataset. The OpenSearch community has been working on read/writer separation. Uber plans to integrate this functionality and evolve the blue/green functionality to this mature solution.

Lastly, we hope to support real-time updates. Currently, our item search relies on batch ingestion to update the vector indices. However, real-time updates are becoming increasingly important as we move towards more dynamic and time-sensitive use cases. We plan to leverage streaming technologies like Apache Flink® to ingest data updates in real-time to achieve this.

Cover Photo Attribution: ”car racing” by lindsayshaver is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Amazon® is a trademark of Amazon.com, Inc. or its affiliates.

Apache Lucene™, Apache Hive™, Apache Flink®, and Apache Spark™ are trademarks of the Apache Software Foundation in the United States and/or other countries. No endorsement by The Apache Software Foundation is implied by the use of these marks.

Meta® is a registered trademark of Meta Inc.

Stay up to date with the latest from Uber Engineering—follow us on LinkedIn for our newest blog posts and insights.

Hao Sun

Hao Sun is a Senior Software Engineer on the Search Platform at Uber. He mainly focuses on expanding vector search capabilities and functionalities. He previously worked on the Kafka Ecosystem team.

Jiasen Xu

Jiasen Xu is a Senior Software Engineer with Uber’s Search Platform team, driving the adoption of vector search technology. He has a broad interest in various technologies, including workflow engines, blockchain, and now semantic search.

Smit Patel

Smit Patel is a Senior Software Engineer on the Search Platform team at Uber. His work is focused on developing features that improve resiliency, performance and user experience.

Anand Kotriwal

Anand Kotriwal is a Senior Software Engineer on the Search Platform team at Uber. His work is focused on developing features that improve user experience, and enhancing search engine efficiency and performance.

Xu Zhang

Xu Zhang is a Senior Staff Engineer at Uber, leading the development of Uber’s vector search within the Real-time Data and Search Platform. Previously, he focused on building robust real-time data platforms to power critical operational insights.

Posted by Hao Sun, Jiasen Xu, Smit Patel, Anand Kotriwal, Xu Zhang