Database Federation: Decentralized and ACL-Compliant Hive™ Databases

February 19 / Global

Introduction

One of Uber’s data warehouses powering the Delivery business outgrew its original design. More than 16,000 Hive datasets and 10 petabytes from multiple business domains lived inside a single, monolithic database—owned and operated by a centralized delivery Data Solutions team. While this one-big-bucket setup once simplified onboarding and discovery, scale and organizational growth turned the same design into a liability. The monolithic design had many limitations.

Shared-Fate Outages

Metadata corruption or resource spikes initiated by one team could cascade across the entire database, disrupting unrelated tier-1 workloads and critical business use cases.

Resource Contention and Noisy Neighbors

Unbounded, ad-hoc datasets and uneven dataset-count growth also competed for the same Metastore, Apache HDFS™, and compute quotas—degrading query latency for everyone.

Operational Bottlenecks

Any database-level task (ACL updates, DDL fixes, TTL enforcement, lineage audits, incident response) had to flow through the central Data Solutions team, slowing mitigation and burdening a single on-call surface.

Governance and Observability Blind Spots

With thousands of heterogeneous datasets in a single namespace, it was hard to apply domain-specific data quality rules, track ownership, and set meaningful alerting thresholds.

Open ACLs

The monolithic database also granted broad read/write permissions to most teams and services, violating least-privilege principles and amplifying the blast radius of accidental or malicious changes.

This blog describes how we addressed these challenges to transform our data warehouse into a secure, scalable, and operationally efficient environment capable of supporting the organization’s evolving data needs.

Migration Challenges

The sheer scale and criticality of the data housed within exacerbated the issues of our monolithic Hive database. Datasets in Hive are foundational for:

- Machine learning algorithms. Powering core functionalities within Uber apps, including recommendations and dynamic pricing.

- Merchant analytics and financial reporting. Providing vital insights and accurate financial statements to Uber Eats merchants.

- Business-critical dashboards. Supporting executive decision-making and operational monitoring across departments.

- Tier-1 internal and external data reporting. Fulfilling crucial reporting requirements for internal stakeholders and external compliance.

- Highly interconnected downstream ecosystem. Each dataset serves thousands of downstream consumers and pipelines, creating a dense dependency graph where issues in a single dataset can cascade into widespread failures.

These challenges required a migration approach that guarantees zero disruption to existing systems.

Migration Principles

We addressed the challenges of the monolithic Hive database by decentralizing datasets into smaller domain or team-specific units. To ensure a successful transition and long-term stability, we established the following design principles.

Zero Downtime and Seamless

Migration of datasets must occur without any interruption to existing data consumers or business operations. This includes uninterrupted access to ML algorithms, analytical dashboards, and reporting systems.

Data Accuracy, Completeness, and Consistency

During and after the decentralization process, the accuracy, completeness, and consistency of all data must be rigorously maintained. No data loss, duplication, or inconsistencies are permissible.

Data Availability

Decentralized datasets must remain highly available to all authorized consumers, with performance equivalent to or better than the previous monolithic setup.

Scalability

The solution should easily scale to many tens of thousands of datasets, enabling independent migration of each, with rollback and retry support, simplifying the onboarding of any number of datasets for migration.

Least-Privilege Access (ACL Compliance)

Each decentralized database should enforce strict ACLs (Access Control Lists), granting only the necessary permissions to specific teams and services. This adheres to the principle of least privilege.

Migration Strategy

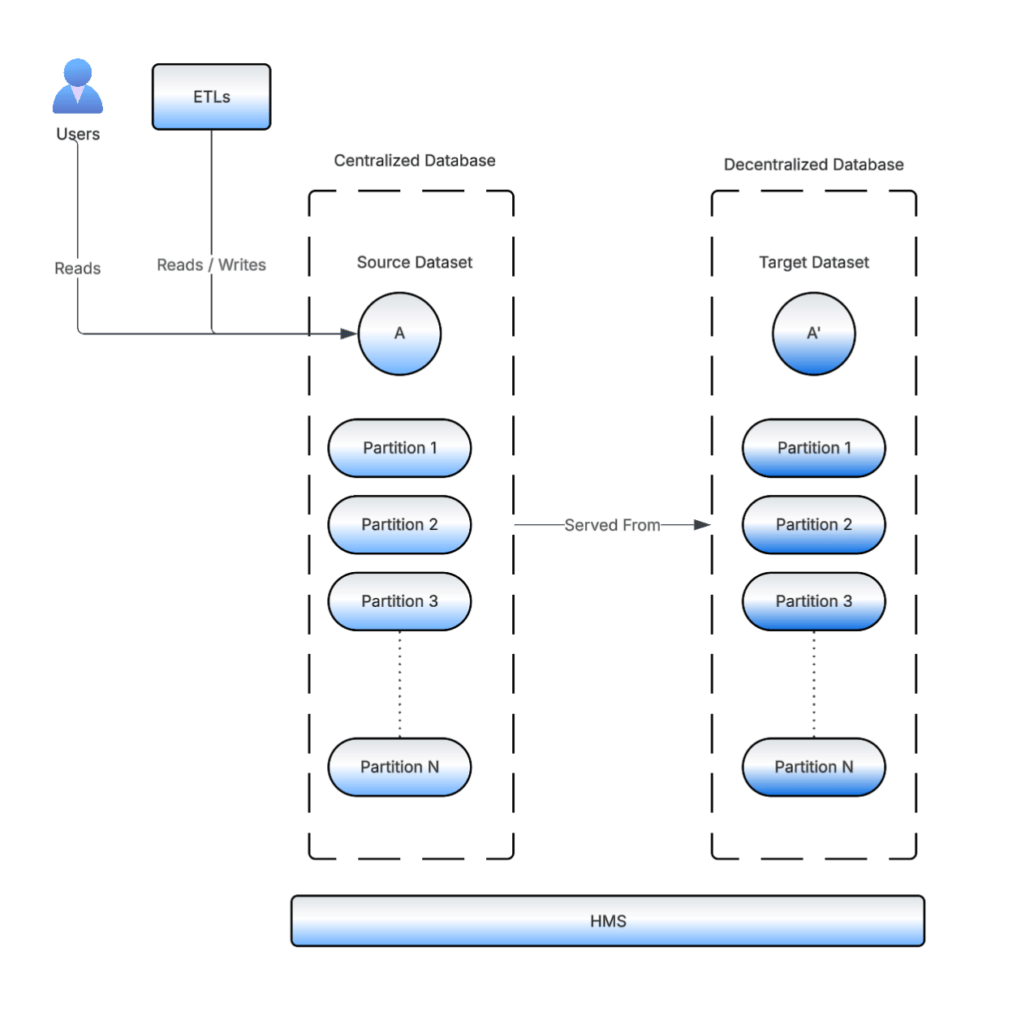

Hive datasets are logical views over data stored in file systems like HDFS. Their link to the underlying data is defined entirely by metadata stored in the HMS (Hive Metastore)—including schema, partitioning, and, most importantly, the HDFS location of the data. For example, a dataset my_dataset may point to /user/hive/warehouse/my_db/my_dataset/.

When Hive or Spark executes a query, it consults the HMS to fetch this metadata and uses the stored HDFS path to read the actual data files.

Leveraging the Pointer Concept

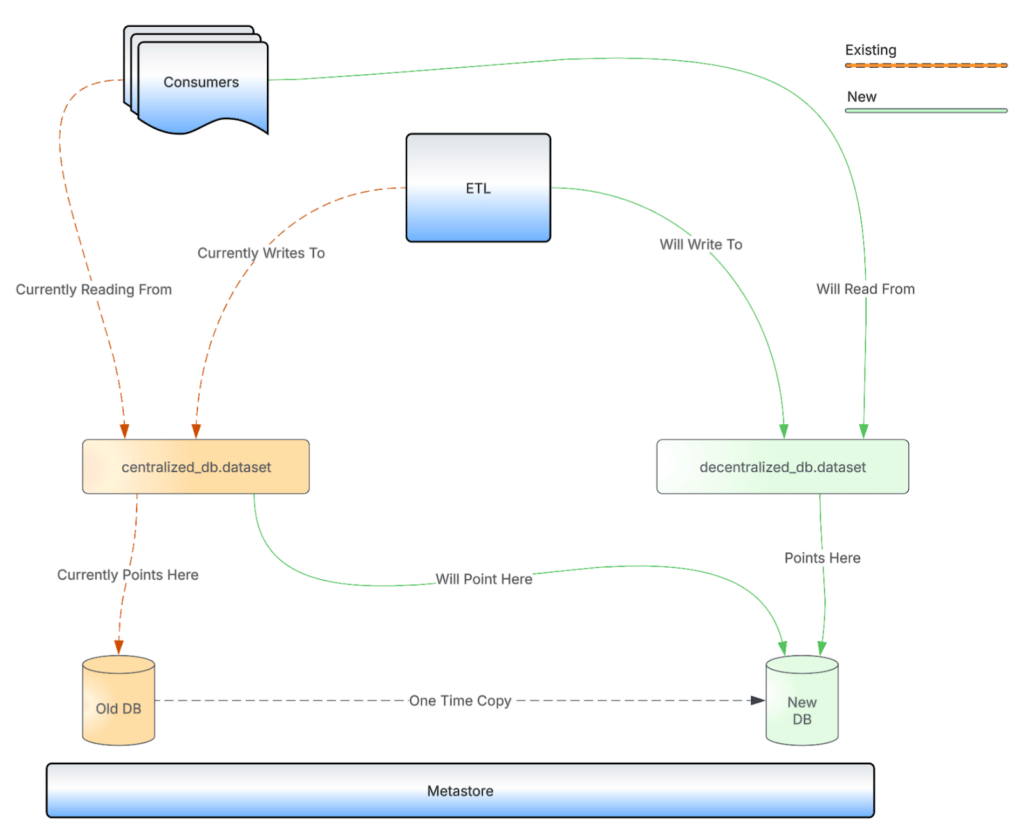

Our solution leverages this pointer concept to facilitate migration without continuous data duplication.

Here’s how it works:

- Original dataset. Initially, an existing dataset in the monolithic database points to its data in a specific HDFS location (like

/old_path/old_db/data_set_A). - Decentralized dataset creation. A new decentralized Hive database and dataset is created with the same schema as the existing dataset. It gets an HDFS location like

/new_path/new_db/data_set_A. A one-time copy of HDFS data is done from the existing dataset to the new dataset’s HDFS location. - Pointer manipulation. The existing dataset’s location in the Hive Metastore is updated to point to the new dataset’s HDFS location. After the migration, the old HDFS location is cleaned up to avoid data duplication.

- Seamless transition. From this point forward, if consumers of the data access it through the new decentralized dataset or the existing dataset, they’re still reading from the same underlying data files.

Advantages of Pointer Manipulation

This approach offers significant advantages:

- Cost savings. Eliminates the need to store duplicate copies of petabytes of data, drastically reducing storage costs.

- Simplified data pipelines. Avoids the complexity and overhead of running two separate data pipelines to keep old and new datasets in sync.

- Zero downtime. Updating a dataset pointer in HMS is a split-second operation, ensuring continuous functioning for critical workloads during migration.

- Data consistency. By having both the old and new datasets point to the same physical data, consistency is inherently maintained.

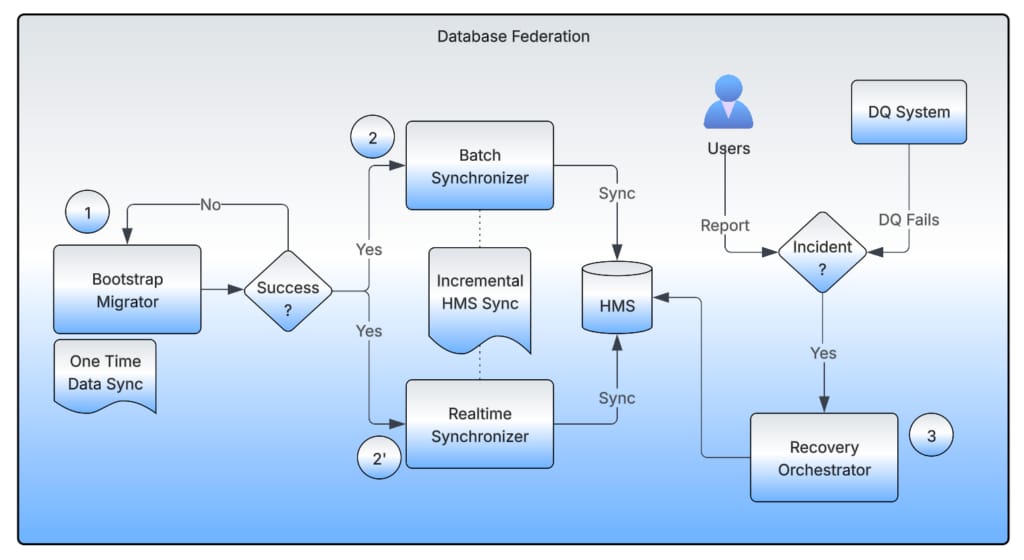

The overall architecture of the data warehouse migration system has four main components:

- Bootstrap Migrator

- Realtime Synchronizer

- Batch Synchronizer

- Recovery Orchestrator

Bootstrap Migrator

The Bootstrap Migrator takes care of the one-time migration of the source dataset to the target dataset.

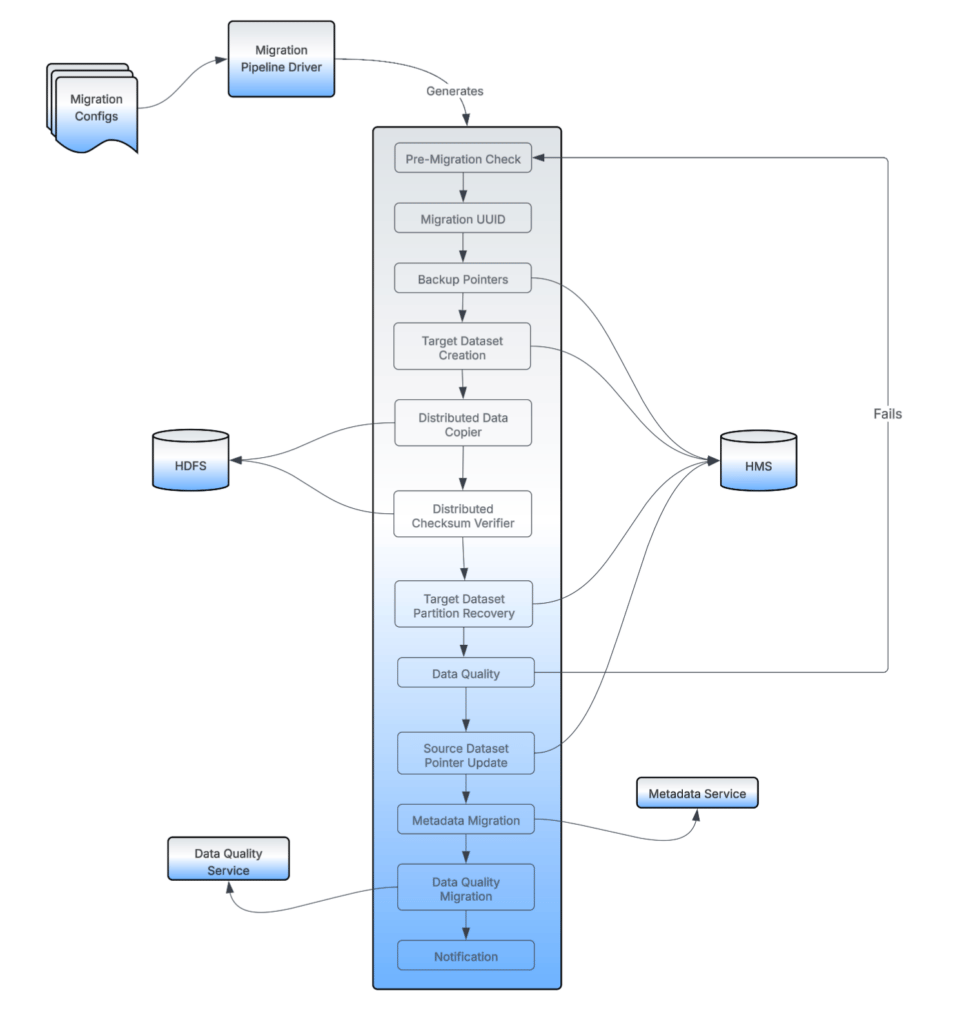

Migration Config

Within the Bootstrap Migrator, the migration config defines the migration direction and ownership. It also controls when to start or stop HMS syncs. For clean and easy maintenance, we created one config per target database.

Migration Pipeline Driver

The Driver reads all the migration configs and generates and cleans up data pipelines, one per dataset to be migrated. Uber’s data pipeline orchestration platform, Piper, runs the Driver at regular intervals to let it parse the new config files or make updates to the existing generated pipelines.

Pre-Migration Checks

Pre-migration checks ensure reliability and correctness of the migrations by implementing the following checks:

- An already migrated dataset isn’t re-attempted for migration. This prevents accidental pipeline triggers.

- Users don’t attempt to migrate a Hive View, which has no physical location of its own.

- Any dataset that points to any other dataset’s HDFS location isn’t attempted for migration, as such cases can corrupt the existing setup of these datasets.

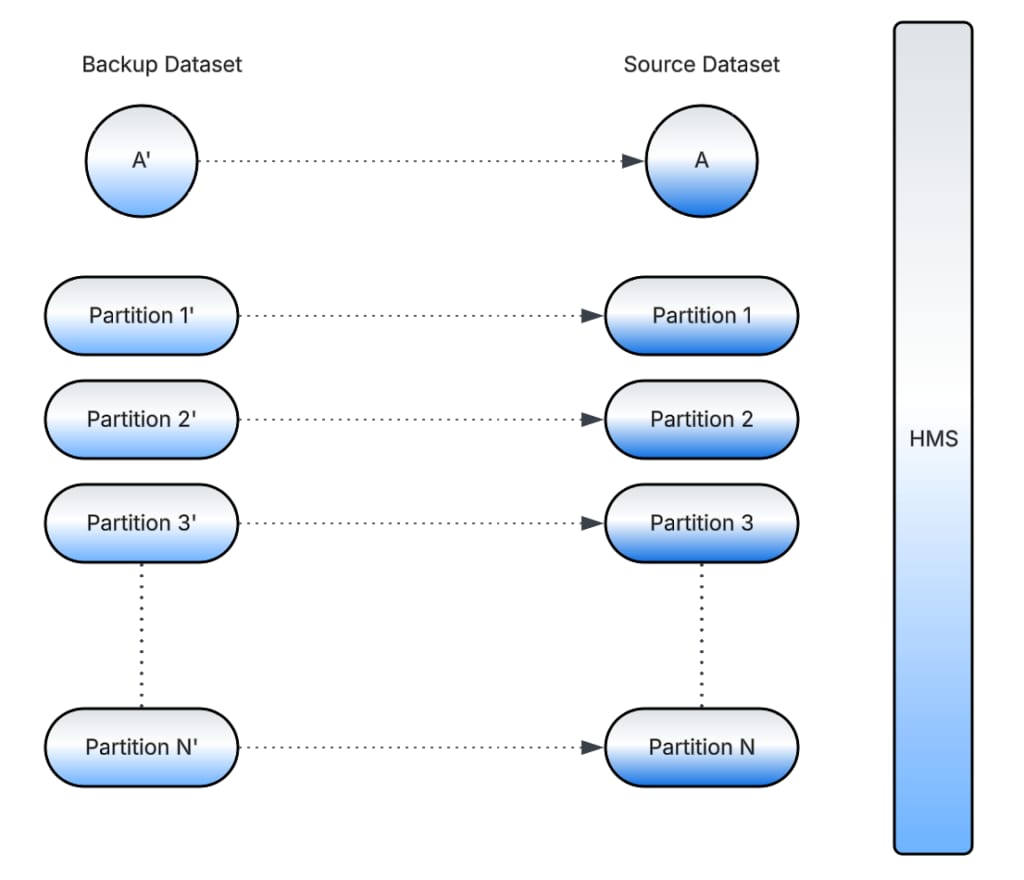

Backup Pointers

It’s important to preserve the pointer state of the source dataset before performing any manipulations. This helps us debug issues, audit migrations, and perform rollbacks in case of incidents.

To do this, we create a backup dataset, which is just a pointer to the source dataset, before the migration starts. The backup dataset is preserved until the overall migration of a dataset is completed and no issues are reported.

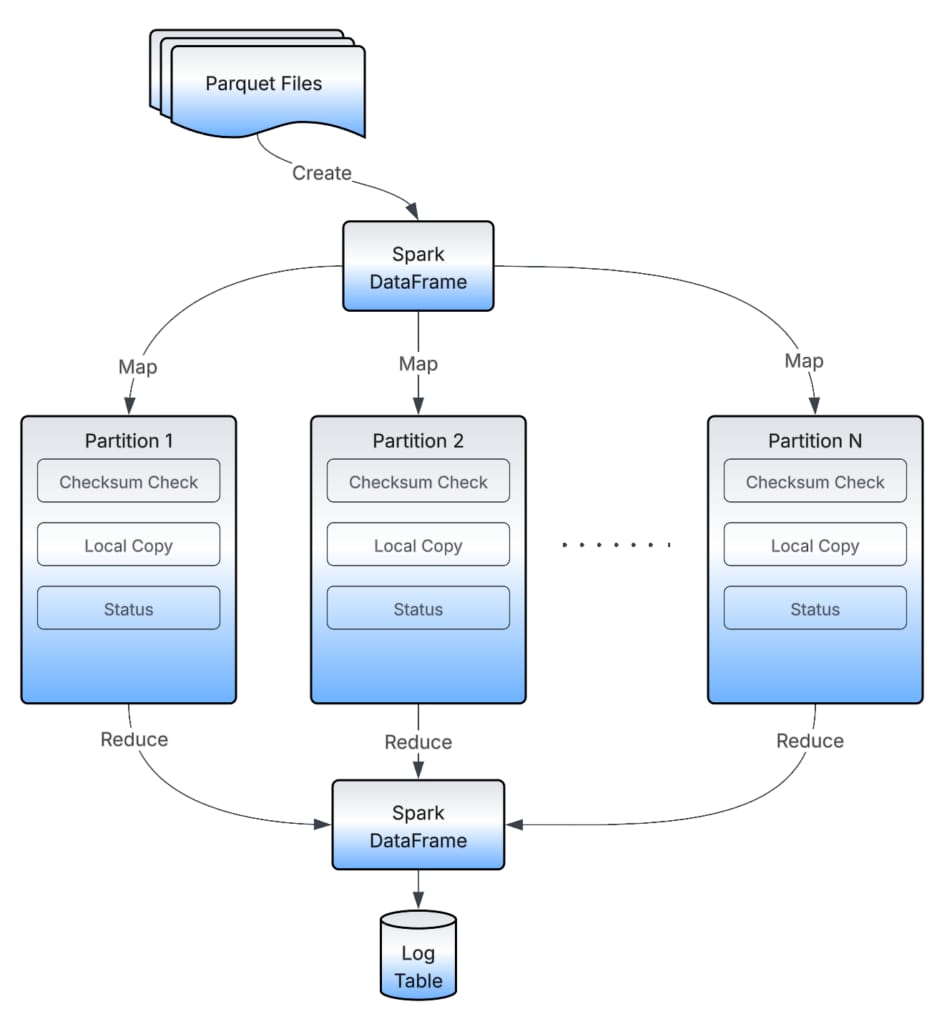

Distributed Data Copier and Checksum Verifier

Distributed Data Copier is a Spark application that looks for the data files in the source dataset’s location that need to be copied to the target dataset. Instead of doing a one-by-one file copy, it distributes the files across all the available executors and then lets each executor run a copy operation. This approach helps scale the copy operation without creating bottlenecks.

Similarly, Distributed Checksum Verifier verifies all copy operations by comparing the checksum of source and target files and records the status of each in a persistent storage for audit purposes.

The Distributed Data Copier acts as a sync utility. Instead of blindly copying files from source to destination, it also takes care of deleting any obsolete directories from the target and deleting any obsolete files from the target. So, it handles cases like if the source partitions get TTLed in between multiple migration attempts. It also backfills the source dataset in between multiple migration attempts.

Target Dataset Location and Partition Recovery

Once the source data is copied to the target location, we recover (add) all the partitions to the target datasets using the source dataset. Once the target dataset has all the partitions added, at this point, it ideally needs to be in the same state in terms of data as the source dataset. So, after this point we start data quality operations.

Data Quality

The Data Quality components perform extensive tests to ensure that both the source and target return the same data across all partitions with no difference at all. This step is the most critical part of the Bootstrap Migrator.

If any check fails, it means that something went wrong in the previous steps or that something changed in the source dataset during the time migration ran. For example, older partitions of a source dataset got TTLed, someone performed a backfill on the source dataset, or the regular ETL pipeline added more partitions to the source dataset.

All of the above impact migration because now the source and target datasets aren’t in the same state. Given our robust design of the Bootstrap Migrator, we just need to rerun the migrator for the impacted dataset.

Source Dataset Pointer Update

Once all the data quality checks pass, we update the source dataset to point to the target dataset, for both its base location and the location of each partition (if the dataset is partitioned). At this point, all the reads and writes exclusively go through the new (target) dataset’s HMS metadata.

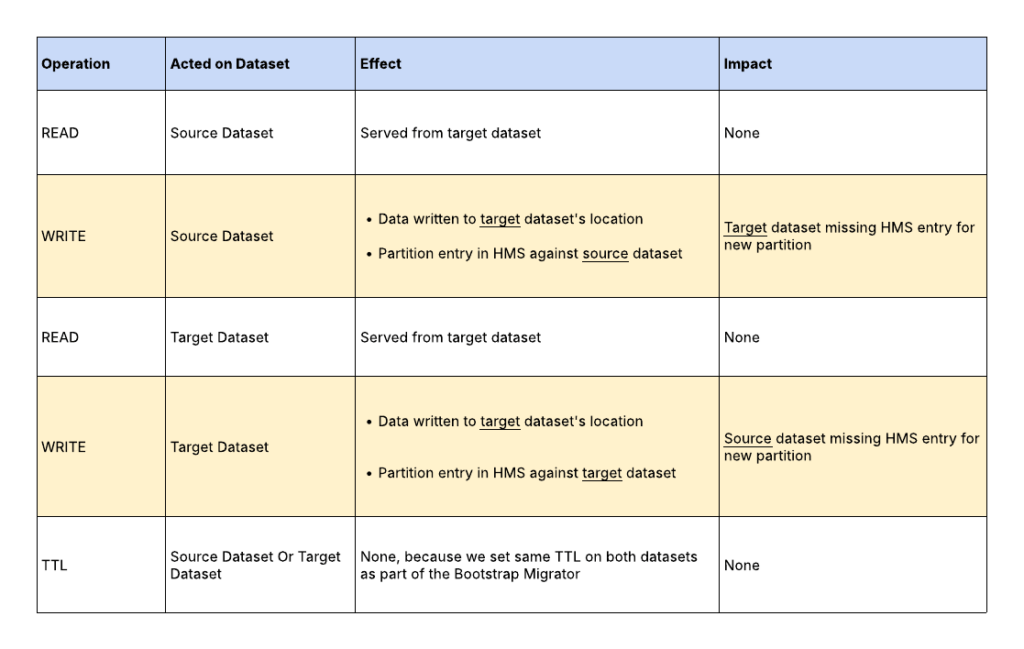

Synchronizers

After the Bootstrap Migrator finishes, every read and write operation on either of the datasets (source or target) is exclusively served from the target dataset. Figure 6 lists different operations and their effect on the datasets.

Every time there’s a WRITE operation on any of the datasets, there’s a need to sync the HMS metadata to the other dataset.

Real-Time Synchronizer

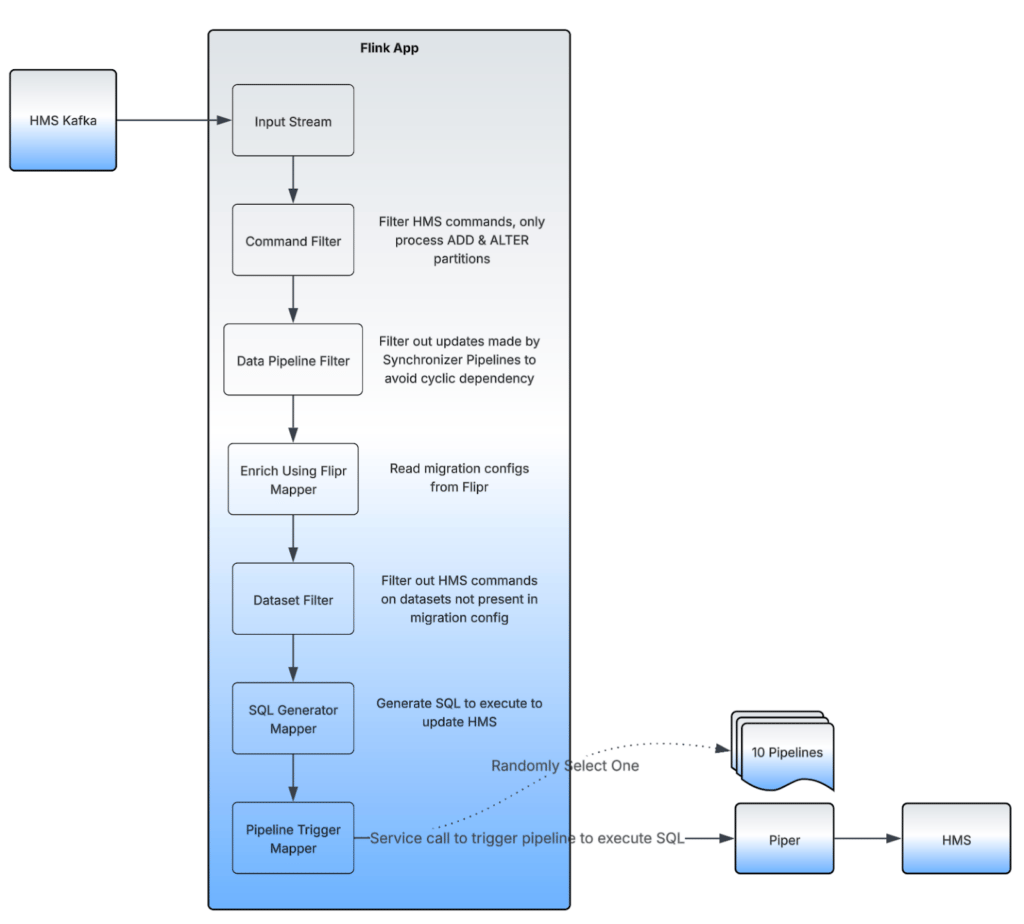

The Real-Time Synchronizer is a combination of an Apache Flink® application and a set of Piper data pipelines. The Flink app listens to real-time HMS updates, and if any of the migration-undergoing datasets have HMS updates, it sends triggers to a Piper data pipeline with commands to execute to keep the source and target datasets in sync.

We rely on a Piper pipeline to talk to HMS. Instead of creating a new Piper pipeline on each trigger from the Flink app, we keep a set of pipelines on standby. To scale the real-time sync process, we keep 10 Piper pipelines in active mode, ready to trigger the HMS sync between any 2 datasets. The payload is sent from the Flink app, and we randomly choose 1 pipeline out of the 10 to be triggered.

Batch Synchronizer

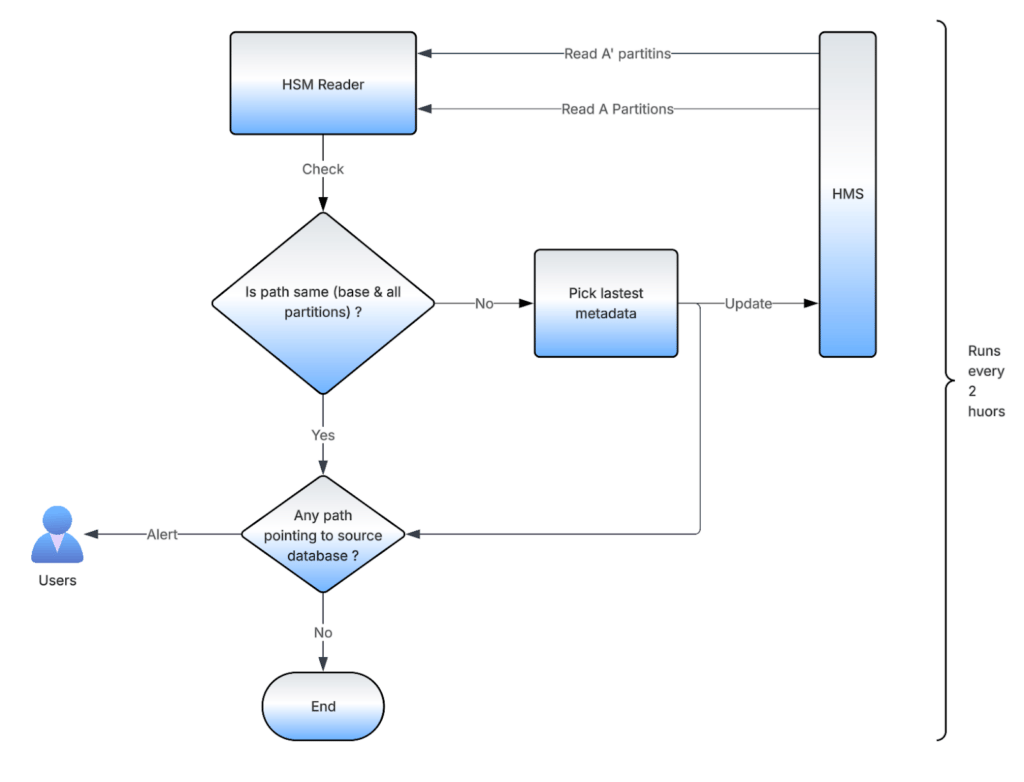

The Batch Synchronizer is created by the Bootstrap Migrator’s Driver for each dataset present in the Migration Config. When the Bootstrap Migration completes for each dataset, users get an email with a link to enable Batch Synchronizer. One enabled, it runs every 2 hours and acts as a fallback to the Real-Time Synchronizer.

The Batch Synchronizer reads all the partition metadata from HMS for the source and target dataset and runs a comparison. If the base path of the datasets isn’t matching, it picks the one that was last updated and applies it on the other dataset. It does the same for all the partition paths (if the dataset is partitioned) as well. It also sends alerts if any of the paths aren’t pointing to the new decentralized database.

The combination of Real-Time and Batch Synchronizer provides eventual consistency in case we miss performing a sync using just the Real-Time Synchronizer.

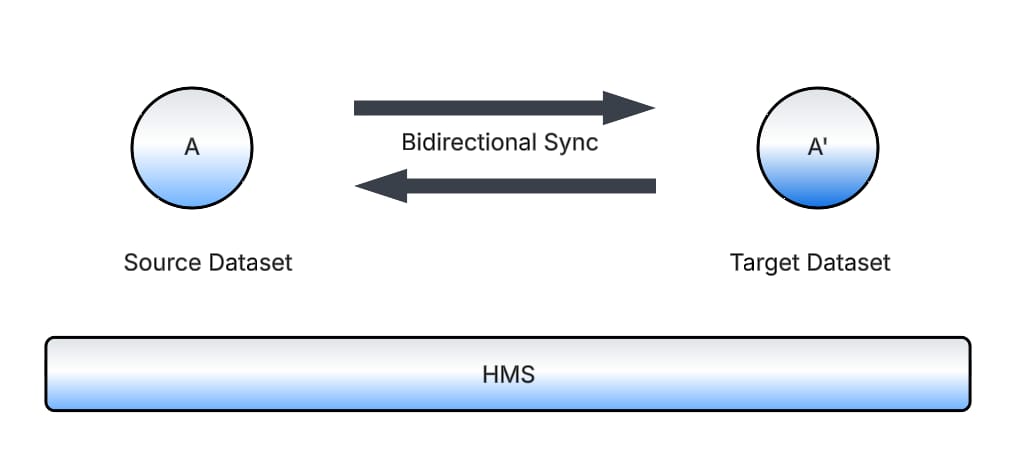

Bidirectional Synchronization

Real-Time and Batch Synchronizers are bidirectional in nature, meaning they take the latest update on either of the datasets and apply it to the other one. This ensures that the latest updates are honored to provide the correct and latest data to consumers, even when the state might not be ideal from a migration perspective. We get alerts for such cases where the team debugs and fixes these problems behind the scenes, without impacting any of the writers or readers of the data.

Rollback Orchestrator

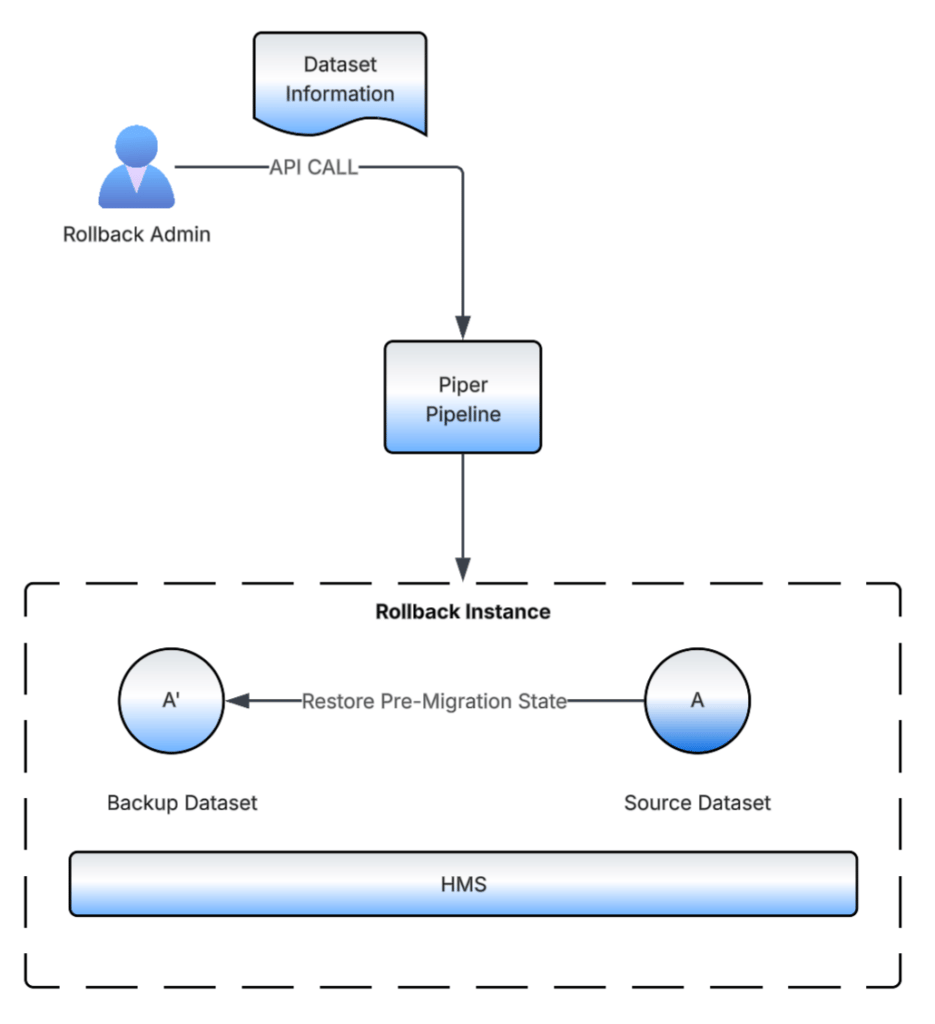

The Rollback Orchestrator is an on-demand trigger-based data pipeline. It receives details about the dataset to be rolled back in the request payload and uses the backup dataset to restore the source dataset to its pre-migration state.

Since rollbacks don’t need the same scale as migrations, we use a single rollback pipeline, but create a new instance for each request to achieve the required isolation.

Conclusion

We migrated thousands of datasets and performed over 7 million HMS sync operations throughout the migration activity. We also saved over 1 petabyte of HDFS disk space as a byproduct by cleaning up stale datasets and avoiding their migration.

With this, we now offer data consumers at Uber decentralized databases, fine-tuned capacities, granular resource management, accountable data operations, and ACL compliance.

Acknowledgments

We’d like to acknowledge Mayank Chandak, Software Engineer II, who built tooling for alerting, automated code changes, added support for migration of Apache Hudi datasets, and performed the migrations. We’d also like to acknowledge Chanchal Gupta, Senior Software Engineer, who built the ACL policy that was adopted for this project. Mayank and Chanchal are part of Uber’s Delivery Data Solutions team.

We also want to recognize Shefali Jaipuriar, Senior Engineering Manager, Delivery Data Solutions, for identifying this burning issue, setting up the project’s vision, and providing her leadership to make it to the finish line.

We thank these Uber teams: Unified Data Quality, Data Lifecycle Management, Metadata and Data Lineage, Data Security, and Hadoop for their contribution to the project by providing tooling and API endpoints for us to integrate, and their support to execute the project smoothly.

Apache®, Apache Spark™, Apache Hive ™, Flink®, Apache Hadoop®, and the star logo are either registered trademarks or trademarks of the Apache Software Foundation in the United States and/or other countries. No endorsement by The Apache Software Foundation is implied by the use of these marks.

Java, MySQL, and NetSuite are registered trademarks of Oracle® and/or its affiliates.

Postgres and PostgreSQL and the Elephant Logo (Slonik) are all registered trademarks of the PostgreSQL Community Association of Canada.

Stay up to date with the latest from Uber Engineering—follow us on LinkedIn for our newest blog posts and insights.

Vijayant Soni

Vijayant is a Senior Software Engineer on Uber’s Delivery Data Solutions team. He recently worked on building a real-time system to enable financial reporting for Uber Eats merchants, significantly improving data quality, reducing freshness SLAs, and reducing serving latencies from hours to within a few minutes for high-volume merchants. He’s currently working on building a platform to detect gaps in clickstream data.

Posted by Vijayant Soni