UBER AND THE AMERICAN WORKER: REMARKS FROM DAVID PLOUFFE

Written byUber launched in San Francisco five years ago. Today, Uber has 1.1 million active drivers on the platform globally. On Tuesday, November 3, Uber Chief Advisor and Board Member David Plouffe gave remarks and participated in a discussion with Vox’s Ezra Klein at the DC tech incubator 1776. Plouffe’s remarks focused on the economic activity generated on and by the Uber platform, what that means to our overall economy—and, most importantly, the people who make up that economy.

You can read his remarks as prepared for delivery below.

Watch the full event:

Remarks as Prepared for Delivery by Uber Chief Advisor David Plouffe

Thank you for inviting me. It’s great to be back in DC, especially at such a thriving and optimistic setting as 1776. And if anyone’s headed to the airport after this, let me know and we can split an uberPOOL.

I want to talk today about the future of work—specifically, the fact that a growing number of people are engaging in flexible and freelance work because of the sharing economy or through on-demand platforms.

While this activity is happening across many platforms, I’ll focus, not surprisingly, on Uber, its impact on the American economy, and its future potential.

The positive effects of ridesharing on congestion, safety and emissions are real and important. Uber can help reduce traffic by taking cars off the road, eliminate transportation deserts by connecting underserved neighborhoods to the heart of a city, and save lives by reducing drunk driving. That has been where much of the focus and debate has been around Uber: its effect on the transportation ecosystem and the incumbent businesses in that ecosystem.

But there has been much less focus on Uber’s broader impact on the economy, especially the scale of that impact. Today I want to focus on the significant economic activity generated by the people who drive and ride with Uber, what that means for the twin challenges of wage stagnation and work-life balance.

To be clear, Uber was not started with the idea it could become a powerful economic engine. It was started by two guys who had trouble finding taxis and wanted to help their friends get around San Francisco a little bit more easily.

Even when I joined Uber 14 months ago, the scale of our two big marketplaces—driver and rider—and the resulting economic impact of the platform was just coming into view.

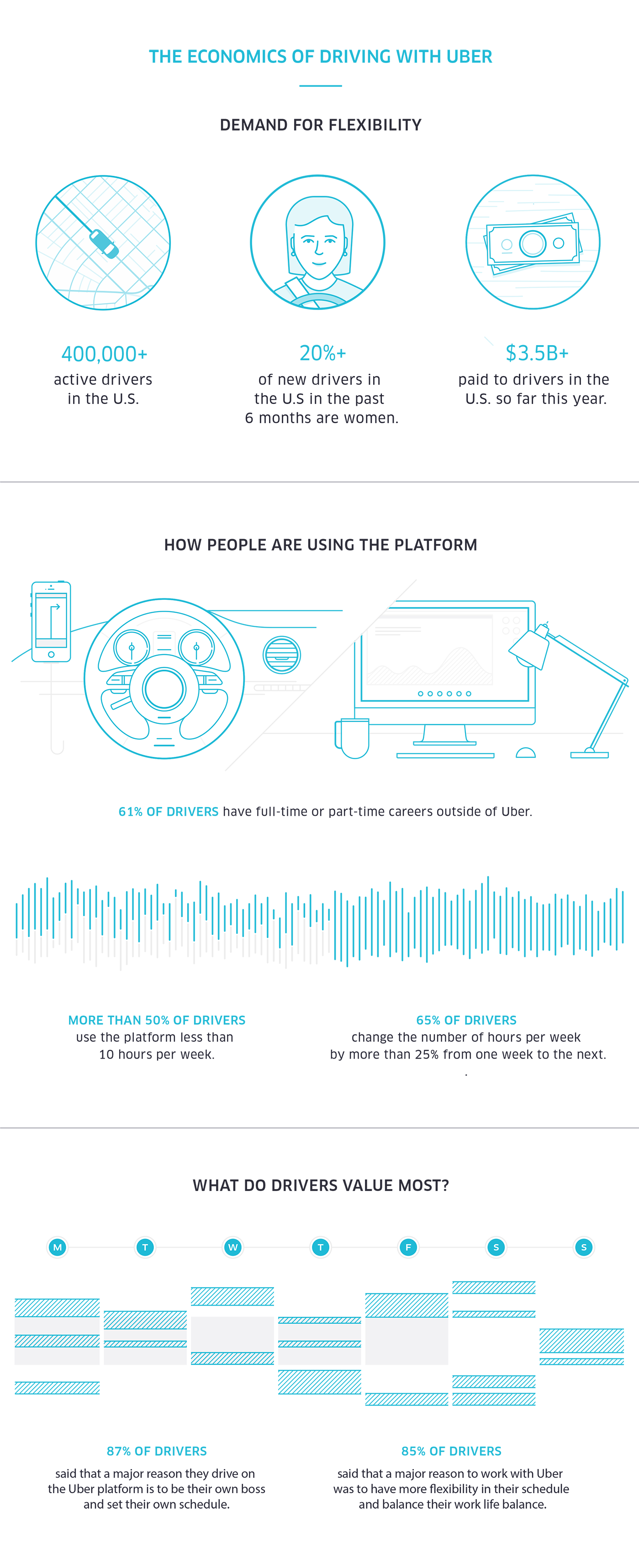

As those markets become larger than even we imagined, we’re discovering that platforms like Uber are boosting the incomes of millions of American families. They’re helping people who are struggling to pay the bills, earn a little extra spending money, or transitioning between jobs. And this is now happening on an unprecedented scale. And it adds up: in 2015, drivers have earned over $3.5 billion.

Uber currently has 1.1 million active drivers on the platform globally. Here in the U.S., there are more than 400,000 active drivers taking at least four trips a month. Many more take only a trip or two a month to earn a little extra cash.

This is important. Most drivers are not making a decision to do this for a lifetime or even for a long time. We are grateful for those who do, but one of the key attractions of the platform is that you don’t need to make a long-term commitment. On average, half of all drivers in the U.S. drive fewer than 10 hours a week. More than 40 percent drive fewer than 8 hours per week. And the average number of hours driven continues to fall; in fact, it’s down more than 10 percent since the beginning of the year. This is crucial: for most people, driving on Uber is not even a part-time job…it’s just driving an hour or two a day, here or there, to help pay the bills.

Basically, Uber offers extra work whenever you want it, and extra money whenever you need it.

Increasingly, people do not talk about becoming “an Uber driver.” It’s much simpler decision: I’m going to make some money while using my car. This is important, because cars are one of the most expensive assets a typical American family buys and maintains—yet they sit unused 96 percent of the time. We only use our cars four percent of the time! It’s hard to think of another expensive item that we use so little. Driving with Uber means people can get more value out of this expensive asset. Driving with Uber means you can turn your car payments into paychecks.

In China we recently launched uberCOMMUTE, which is a way to share your car as you travel to and from your job. Eventually, you can imagine a world in which people turn on the Uber app while running errands or visiting friends, making a little extra money as they move around town. Over time that would cut congestion by reducing the number of people owning cars, and would lower the cost of living for those who do own a car.

The reality today is that many, many people are looking for more income, which is crucial in today’s economy. It’s clear that while the economy is growing and recovering, there are still too many people who aren’t feeling the full effects of that recovery, and too many people who are still looking for work.

I have consumed about as much political research in the last ten years as anyone in the world. And good political research, like good business research, yields the most useful insights when it’s not about politics or business but simply getting the best understanding about how people are living their lives, their challenges and aspirations. What that research showed, universally and unequivocally, is that most people in America say they have too little money and too little time. The two are closely connected—and they’d like more control of both.

Uber and platforms like it helps solve for both of these pain points. In a world where more people than ever before are struggling to balance work, family, and bills they can’t pay, ridesharing is a way to put money back in your pocket and time back on your schedule.

Perhaps the biggest economic challenge of our time is stagnant wages, which are growing at around the same rate as they did in 2010. And real median household incomes are down 7.2 percent since the turn of the century.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics also estimates that 20 million Americans are forced to work part-time for “non-economic reasons” like caring for a family member or education. So, again, it’s not that people don’t need the money. On the contrary: 47 percent of people in the U.S. say they would struggle to handle an unexpected $400 bill, and a third of those said they would have to borrow to pay it.

Just look at the numbers on student loan debt and you can understand why: more than 43 million Americans now owe $1.2 trillion on their student loans. That’s $27,000 per person on average. And only 37 percent of borrowers are making payments on time and reducing their loan balances.

In essence, then, people tell us that they drive with Uber in order to get a pay raise that they’ve been denied for years. Or they do it to help themselves when they get in a tight spot. And drivers consistently report what they prize most about the Uber platform is the flexibility of being able to work around job, family, school, and other obligations.

In fact, nearly 90 percent of drivers choose Uber because they want to be their own boss and set their own schedule. In other words, they want work that fits around their life—not the other way around. Around 65 percent vary their hours from week to week by more than 25 percent. They themselves don’t have a set schedule week to week; they fit Uber around everything else.

That means you’re more likely to find someone who drives 10 hours one week and zero hours the next week than someone who works every Tuesday and Wednesday from 5 to 10 pm. Indeed, there is another debate right now about the practice of on-call scheduling—employers minimizing their labor costs by keeping workers on an unpredictable and ever-changing schedule. With Uber, there is no schedule. Ever.

This flexibility is particularly important for women who have been leaving the workforce. The percentage of working-age women in the workforce peaked in 1999 at 74 percent but has fallen to around to 69 percent today. The U.S. has actually been outpaced by Japan, which historically had relatively few women working.

Lack of flexibility is a key culprit in this trend, which is why we’re seeing so many people leap at the opportunity to set their own work schedules.

I’ll give you a few examples. There’s a small business owner from Cincinnati named Victoria who started driving with Uber because the economy was rough. She needed to make additional income on top of her business profits so that she could give her kids a debt-free college education.

There’s also Suzanne, an actor living in Jersey City, who got a car through Uber’s Vehicle Solutions Program, which helps people who don’t have a qualifying car get one and get on the road. Now she’s making more money, and can get to any audition—because she decides when to work or not work.

Maria, a special ed teacher in Denver, decided to drive just an hour or two a week in her spare time so that she could save money for a vacation to Ft. Lauderdale. And that’s all it took.

The numbers show just how attractive this type of work is to people around the country. Today more than 48,000 people drive with Uber in Los Angeles; more than 10,000 in Philadelphia; 10,000 in Austin; over 15,000 in Atlanta; and 35,000 in Chicago and 27,000 here in DC. Most of that growth is in the last two years. Think about that. If a factory suddenly appeared in a major American city and created thousands of jobs in just two years, there would be ticker-tape parades.

It’s fascinating to look at some of our fastest-growing driver demographics. Recent retirees are streaming onto the platform. They need or want additional money and are looking to remain active, which is one reason we have a partnership with AARP’s Life Reimagined project.

Another growing cohort is stay-at-home parents. Many of you here who have used Uber have probably met someone in this category. They drop their kids off at school and then drive for a few hours in the morning and early afternoon. For example, a mom named Kim in Los Angeles quit her job in real estate to spend more time with and care for her daughter, who has epilepsy. She now drives with Uber about 10 hours a week to add to her family’s income.

A dad in Seattle also left job to partner with Uber and take care of his kids while his wife goes back to school. He said, “My three children are my first and last customers.”

And almost 40,000 drivers have joined Uber as part of a program we call uberMILITARY. These veterans come home after serving their country, and they can drive while they figure out what’s next. To the surprise of no one, they are also among our highest-rated drivers.

That transitional use case is really important. Uber drivers tend to over-index in high unemployment areas. Think about it: you lose your job or have your hours cut. You have housing and car payments due. But you can put your car to work and be on the road earning money in matter of days.

This also saves the government money in terms of benefits, because of course people would rather work than receive unemployment. And Uber allows you to go to job interviews, work on skills, and build your network. Because you have no set schedule, it’s really the perfect safety net that helps you stabilize while looking for a full-time job. In fact, about a third of drivers said they used Uber to earn money while looking for a job.

Now, that’s in the U.S. economy, where the primary issue we face today is underemployment and wage stagnation. But Uber can help expand work opportunities in economies with high unemployment rates as well. In France, 25 percent of our over 10,000 drivers were unemployed before driving with Uber, and around 40 percent of those had been out of work for more than a year.

Now, the positive economic benefits are not just on driver side. Ridesharing also has a powerful effect on cities, their economies and the people who live in them.

Take small businesses, for example. With Uber, you no longer need to be in a particular neighborhood or on a particular street to get customers, and potential customers don’t need a car (or a taxi) to reach you. Uber drops people off everywhere in the city at the press of a button. In Chicago, we looked at data on Uber trips with Yelp’s database of local businesses and estimated that around one in three Uber trips originates or ends at an independent Chicago business.

So it’s easier to attract customers even if you are not in higher priced retail areas. And the same goes for people living in areas that have been traditionally underserved by public transit and taxis.

There are transportation deserts in every city in the world. Some are due to the happenstance of planning, and some because of simple geography. But most of them tend to occur in lower-income areas.

Research has demonstrated a strong connection between poverty and the unavailability or high cost of transportation. A long-term Harvard study found that the single biggest factor in determining whether someone can escape poverty is not crime rates or elementary school test scores, but commuting time.

Uber can quite literally help transport people out of poverty, offering people affordable rides whenever, wherever they need one. Half of trips in Chicago begin or end in an underserved neighborhood, like the South and West Side.

Nearly a third of trips in New York are to, from or within the outer boroughs, compared to just 10 percent of taxi trips. In Boston, up to 35 percent of residents in traditionally underserved neighborhoods like South Dorchester, Mattapan and Roslindale were previously unable to get a taxi within 20 minutes of a request, compared to Uber’s 96 percent reliability.

And here in Washington, trips to and from Wards 7 and 8 have grown more than 800 percent year over year.

Take the transportation situation in Fort Davis, a neighborhood in Ward 7. Say you need to get to Naylor Road, the nearest Metro station to the Fort Davis Recreation Center.

You would have to walk around five minutes to the bus stop at Southern Avenue and 41st Street SE, and ride the F14 bus for 10 or 12 minutes and 9 stops. That’s if you don’t have to wait for the bus, which can take up to 30 minutes.

All in all, it would take around 20 to 50 minutes to even get to the Metro, depending on when you catch the bus. Yesterday I opened the Uber app and plugged in the Fort Davis Recreation Center. The estimated pickup time for an uberPOOL was 4 minutes.

We see many people using ridesharing to save a half hour and a few dollars on their commutes, often connecting to public transit. In Portland, Oregon, for example, nearly one in four trips in the city’s suburbs began or ended near a commuter rail station.

For people in transportation deserts who have too little time and too little money, an affordable ride at the press of a button can feel like a small miracle. Or, as our Vice President would say, it’s a Big Effing Deal.

And it’s important to note that that you can get the same service in Marion Barry’s old City Council district as on K Street. You push a button get a ride in around 3 minutes on average, no matter what you look like or where you live. The days of transportation discrimination are over.

Obviously, we are a business, not a non-profit. But we believe platforms like Uber are making a real and growing difference when it comes to the challenges of wage stagnation and underemployment. There is also big impact on creating more flexible work, which has been a chief policy goal for many over the last few decades.

With platforms like Uber, you can fit work around the rest of your life. And ridesharing is making transportation more affordable for low-income residents all across the world. These are powerful economic effects—and by the way, they’re economic benefits that require zero government funding. We are not asking for special tax breaks like those who want to build a factory or headquarters in a city often do. We’re simply asking cities to allow their citizens to use their personal assets—their cars—to make money by driving their fellow citizens around their city.

There are of course valid questions about what adjustments policymakers will have to make if more people work for themselves, on platforms like Uber or others. First, this is not just about new digital platforms. Many industries have had high rates of independent workers for decades.

Around 80 percent of real estate agents were independent in 2014; 64 percent of registered financial advisors are estimated to independent; even 20 percent of emergency room doctors are estimated to be independent. And yes, 90 percent of taxi drivers are estimated to be independent contractors. So any ideas or policy proposals will inevitably affect these other industries and must take these equities into account.

We are eager to be a part of that debate.

But today, we wanted for the first time to lay out holistically a look at how Uber and platforms like it are positively affecting the economy—and, more importantly, the people who make up that economy. Some approach the on-demand economy as if it’s a problem that needs solving.

But when you look at the full picture of how people are truly using these platforms, it’s clear that this is much more of an opportunity to be seized than a problem to be solved. The question is: how can we build on and strengthen these important gains? We look forward to that debate and will engage in it on behalf of the tens of millions of people over the coming years who will benefit from these innovations.